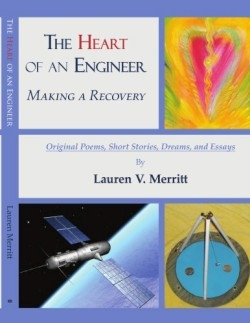

The Heart of an Engineer

Making a Recovery

Merritt spends this volume on a search for God love and a suitable dance partner. Filled with limericks ballads and metrical poetry the volume chronicles Merritt’s life as an aerospace engineer dancer man with Parkinson’s disease and would-be lover—in essence his life. The effect is much like an acquaintance relating a dream—surely fascinating for the teller but less so for the listener.

Merritt earned thirteen patents as an aerospace engineer an awesome feat and one that suggests science might serve as a compelling metaphor in the work. Unfortunately what figurative language there is tends to rely on pedestrian images: boats for journeys dances for relationships flying eagles for freedom. Merritt also ignores opportunities for the kind of specific detail that makes good writing live on the page. For instance in “Moving On” a poem about a pioneer family moving West he writes:

In the courtyard the wagons sit

Piled high with household wares

And little things

Each quite worthless by itself

But together describing

The essence of a family

Soon to be moving on.

Merritt might have followed the hallowed dictum of creative writing: show don’t tell. He might have gathered each little thing: a rag doll a chewed red ball a tin of hair cream a sifter for flour and the family Bible for instance. Rather than telling the reader these things add up to a family he might have shown that. In “White Water Raft” he delivers a much stronger line: “Rubber tubes made hard with air.” The line is both tactile and visual an effect for which the poet ought to strive more often.

Merritt also includes little stories written for his grandson which are cute and a series of dreams and their subsequent analysis. The dreams themselves and the analysis are interesting for content rather than literary value. Merritt had electrodes implanted in his brain for his Parkinson’s and he undergoes dream therapy. Unfortunately this is a small portion of the book which is not explored in a substantive manner.

For many poetry serves as a kind of therapy and certainly that is the case here. The poet used the page as a cathartic release a self-reflective effort. Regrettably the poems do not reflect a critical eye or an attempt to create an art that looks beyond the immediate self. To access the universal to which all art aspires the work must open itself to an audience greater than one.

Reviewed by

Camille-Yvette Welsch

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.