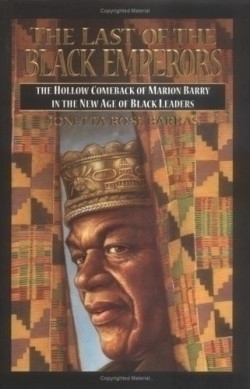

The Last of the Black Emperors

The Hollow Comeback of Marion Barry in the New Age of Black Leaders

Promising to continue to serve in some public capacity, Marion Barry, Washington, D.C.‘s colorful and wildly popular political Lazarus, held a press conference in late

May to announce he won’t make a fifth bid as mayor. It was a moment all but foreseen by Jonetta Rose Barras in The Last of the Black Emperors. Barras would argue that if Barry had not voluntarily stepped aside he would have met an embarrassing defeat at the polls this year.

Polls showed Washington voters viewed Barry as an obstacle to progress. Barras points to other, larger pressures: The old guard of black, civil rights-era mayors who used the language of protest and confrontation to move voters in Detroit, Cleveland and Chicago, are giving way to a new breed of leaders who “embrace African American culture but are not imprisoned by it.”

Barras traces Barry’s trajectory through the politics of the racially polarized city, which started full of promise, empowering black voters while engendering the city with hope, new ideas and energy. But her main focus is on the period of the 1990s, the era of Barry’s decline when he received blame for racial divisiveness, fiscal mismanagement and a paucity of fresh programs.

Barras probes Barry’s popularity within the black community and culture, from his political embodiment of the tendency to elevate and celebrate defiance of “the system” to his personal charisma. A columnist and former reporter for the Washington Times, Barras places Barry among a group of black political leaders of the past quarter century — Detroit’s former Mayor Coleman Young is another — who fought their way to posts of power and influence and enjoyed an almost complete identification with the working class and poor constituents of the urban areas they ruled. Thus, the voters in Washington’s Ward 8 happily and handily re-elected Barry to the city council in 1992 following his conviction and imprisonment for narcotics possession.

Barry’s redemption and resurrection was short-lived. Barras argues that the opportunity and goodwill he and other black mayors once held out to constituents produced “mostly temporary and fleeting improvements…Some American cities were in worse shape in 1997 than they were in 1967.” This old guard is being nudged from power by a new generation of black leaders who “combine corporate savvy and management acumen with street smarts,” leaders who “understand the nuances of racism…but do not wear it as their albatross.” In the post-civil rights era, Barras writes, black voters crave a new style of leadership, one that substitutes substance for the old symbolism.

Reviewed by

John Wark

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.