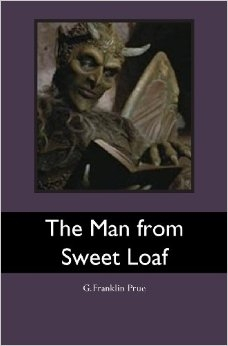

The Man from Sweet Loaf

Though some elements are magical, Prue speaks the truth about the treatment of African Americans and veterans in this disquieting, mesmeric read.

G.Franklin Prue returns with a dark, frequently surreal novel that follows Sam Murphy, a good-natured but haunted African-American Vietnam veteran, through his decades-long struggle for redemption. These pages are at once a cultural commentary, a trip through the uncanny, and a convoluted love story. The end result is both intriguing and disturbing.

The novel opens on Sam’s affair with Mabel, a beautiful woman who is generous in her affections. Sam, now over a decade out from the war, is ambling toward a more stable life, but he still handles his demons in a frenetic manner. There’s some philandering; there’s a little skimming from the profits of his employer’s stores. Sam’s police-officer brother, Ray, is a continual presence, pulling Sam back toward prewar paths and encouraging him to reconcile with their ailing father.

Encounters with the elder Murphy prove to be the novel’s oddest moments. Sam is prone to regarding those around him a bit colorfully, which the reader is led to believe is a result of stress from the war, but his father receives the harshest treatment. Sam sees him as a gargoyle, complete with wings and a fire-emitting tongue. Sam can’t forgive his father for the traumas of his childhood; not only were drugs always around, but Sam also witnessed his mother’s sad death.

Eventual redemption comes with the introduction of Myrthe, an exotic Haitian woman. Sam, who’s lost Mabel to his brother, falls for Myrthe quickly and resolves to rescue her from a dangerous, sexually charged situation at the embassy where she’s employed. After a hundred pages of buildup, this rescue is tidily effected. The novel then skips forward five years to find Sam a happily married family man, his life revolving around his and Myrthe’s young daughter, all while finally holding a steady job.

The shift is jarring, if welcome. The stark realism of the opening pages—from the racism of local bosses to the continual cycle of death that greets recovering neighborhood vets—gives way to lighter, if still troubled, scenes.

The prose throughout is written in a staccato style, evocative and swift, but is less unsettling in the latter half: “Murky grey waters wash up around their shoes. Snowflakes float, follow them around the lake of benches; tall, hot lamp lights. Horizon of cold stars above their heads.” Sam, Myrthe, Ray, and Mabel all find their way into a contented family life and form an unlikely, but operative, unit.

Though the magical elements and fevered perspectives throughout render any consistent realism elusive, the novel contains enough truth—regarding urban life for African Americans at midcentury and the treatment of veterans in later decades—to leave the reader feeling edified. The musicality of Prue’s lines increases both the weirdness and the appeal of these pages. The Man from Sweet Loaf is a fascinating yet unsettling read.

Reviewed by

Michelle Anne Schingler

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.