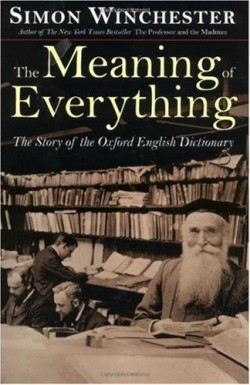

The Meaning of Everything

The Story of the Oxford English Dictionary

“I have to state that Philology, both Comparative and special, has been my favourite pursuit,” said James Murray.

Never before or since has an army of amateurs produced so vast and professional a product as the OED, the Mount Everest of lexicography. In his splendid account of how the world’s most comprehensive and word-rich language was brought to book, the author, who wrote the highly acclaimed The Map That Changed the World and Krakatoa, never neglects the quintessential Englishness of the mighty project. In 1857, a private society of engaging eccentrics conceived of a dictionary based not on mere definitions but illustrative word histories.

Under its first editor, an erstwhile guerilla turned Anglican bishop, the project was almost stillborn; under the second, an expert on Icelandic dialects who succumbed to tuberculosis at age thirty-one, murmuring “Tomorrow I must begin Sanskrit,” it languished. Under the third, a hyperactive near-genius who founded eight scholarly societies, took shop-girls sculling on the Thames (eyeing their wet and clinging blouses), and demonstrated in front of 10 Downing Street, the OED nearly died: vital raw material-the volunteer readers’ innumerable word-usage examples-was causally “lost.”

The project took on new life in 1882 with the usual deus ex machina of English enterprises, a brilliant self-educated Scot. James Murray devoted selfless years to the project, dying in harness in 1915, aged seventy-eight, having fathered eleven child-helpers. He demanded impeccable standards, silenced critics, and foiled a threatened hijacking of the enterprise. Winchester’s account of Murray’s magnificent achievement would be impossible to better in the same compass.

The OED consumed £375,000 over 78 years, far beyond its original budget for money and time; the last volumes came out in 1928. In all, an unrivaled 414, 825 headwords and 1,827,306 illustrative quotations. At first the American Webster’s Dictionary was a dangerous competitor. However, as Winchester generously acknowledges, numerous Americans were gifted and productive contributors in the OED’s surge to lexicographic leadership. He recounts William Chester Minor’s strange, uniquely tragic life and unmatched contribution in The Professor and the Madman; the story of the brilliant hermit Fitzedward Hall, equally strange but less tragic, is yet to be told.

The making of the OED ran like a tingling intellectual pulse through almost a century. It involved thousands of contributors worldwide (many of outstanding gifts and great human interest); it required winning over an often obstructive Oxford University Press that finally produced a dictionary unrivaled in format and design, thanks to skilled, dedicated printers and pressmen. It’s a great story brilliantly told, complete with a mini-history of the language and vignettes of earlier dictionary-makers. The publisher deserves grateful recognition for a finely designed, handsomely illustrated, and well-produced volume.

Reviewed by

Peter Skinner

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.