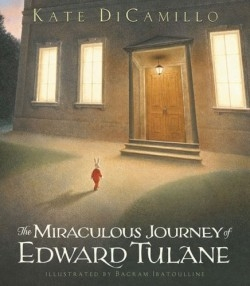

The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane

A story about the thoughts and feelings of a toy bunny can’t help but call to mind The Velveteen Rabbit, that well-loved tale of a battered, longsuffering stuffed animal who longs to be real. Only a page or two of this book, however, is enough to dismiss the notion of much similarity between the two characters. Edward is a dapper porcelain rabbit who knows himself—with the possible exception of whiskers “of uncertain origin”—to be as grand a specimen as ever there was. Spending his days facing the picture window, he prefers winter, when the sun sets early and he can see his reflection in the glass. He sits at the family dinner table each evening, clad in custom-made outfits of the finest fabrics.

The pampered, privileged rabbit suffers the occasional indignity, as when a maid vacuums his ears, handling him “as cavalierly as an inanimate object,” or when he is picked up and shaken in the jaws of an errant dog. Saved by his mistress’s mother’s shouting “Drop it!,” Edward feels his ego to be more bruised than his aching head: he’d been referred to as “it!”

The author, whose children’s stories include the 2001 Newberry Honor book Because of Winn-Dixie, paints Edward’s circumstances with enough pathos and humor to render him charming, yet shows enough of his heartless self-importance to keep from being maudlin. It is Edward’s character flaws, like the foibles of A.A. Milne’s anthropomorphized animals, that make him real. Pompously aloof, Edward tolerates the adoration of his ten-year-old mistress with no compunction about his lack of reciprocal affection for her. He is merely puzzled by the story told by the girl’s grandmother: a princess who doesn’t love is spellbound by an evil witch—without redemption. When the girl decries the unhappy ending, her grandmother shrugs and replies: “How can a story end happily if there is no love?”

This is DiCamillo’s theme, and the miracle of Edward Tulane’s journey is the miracle of learning to love. Through repeated accidents of abandonment and cold dismissals, Edward gradually experiences emotion: fear, despair, gratitude, humility. He finds a measure of understanding: the princess in the grandmother’s story, he realizes, was punished because she didn’t love. To DiCamillo’s credit, appreciating the importance of love doesn’t magically plant that feeling in Edward’s heart. It does engender sensitivity, however, and Edward reveals himself to be a compassionate listener: “And in his listening, his heart opened wide and then wider still.”

When he is picked up by a poverty-stricken boy with a terminally ill little sister and an abusive father, the story turns a bit too sentimental, but this small departure from DiCamillo’s typically comfortable balance between sweetness and wit is easily forgiven. The story ends with a satisfying twist of fate, completing a tale that is both delightful and moving.

Reviewed by

Bonnie Deigh

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.