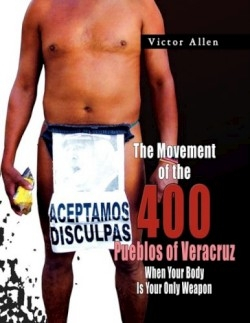

The Movement of the 400 Pueblos of Veracruz

When Your Body is Your Only Weapon

Public demonstrations are commonplace in the Mexico City, but nude and scantily clad protesters wearing politician’s faces emblazoned across loincloths are startling anywhere on earth, especially in a nation where modesty and Catholic mores are the norm. This sensitive and interesting photo essay on the 400 Pueblos members explains how a bunch of poor farmers ended up dancing and passing out literature to passersby while naked or nearly so.

In 1982, the residents of several villages in the state of Veracruz who had farmed public lands for a decade were abruptly ordered to move by the local authorities. Twice a year for the next ten years, the farm families, organized as the 400 Pueblos Movement, traveled to the Mexican capital and lived in tent villages between daily protests on the elegant, shop-lined Paseo de la Reforma. In 2002, the same Veracruz Governor who had ordered the removal of the pueblos from their lands was elected to the Federal Senate. To increase the pressure on the central government, the protesters decided to use their only remaining resource, their own bodies, to get attention for their cause. Until they finally achieved land reforms and other concessions six and a half years later, the gutsiest members of the 400 Pueblos protested nude or wearing only underwear or a loincloth. They did so twice a day, every day, no matter the weather. Women climbed up on platforms, men posed on homemade crucifixes, and drummers accompanied a phalanx of bronzed, chanting farmers of all ages to draw attention to their cause.

Author Victor Allen documented the last six months of the 400 Pueblos protest and he has produced a respectful, fascinating portrait of an intriguing social movement. These folks transformed from the humblest members of the country to some of its most powerful and determined citizens. They were willing to do anything within the bounds of non-violent protest to advance their cause, and they risked the social taboo of public nudity to do so.

Allen’s photos are not prurient—they focus on the strength of weather-lined faces, hard-working hands and determined expressions—but this book is not intended for children. It includes many shots of naked hindquarters and some full-frontal nudes are visible in the background of several photos. This is not art photography (some images are decidedly unsharp) as much as photojournalistic documentation of a little-known but interesting and successful social experiment. Allen’s captions and text are clearly sympathetic toward his subject, and the whole makes for an absorbing read.

The book includes a few pages of portraits of clothed protestors just before they disrobed for their scheduled protest. These images provide an inspired contrast with the vigor of the nude protest shots. Some photos of the Mexican police officers surrounding the protesters would have been interesting to see, and Allen missed an opportunity to show a comparison of the defenseless protesters contrasted with fully-armed riot police.

This book would be informative for readers interested in Mexican culture and history, grassroots organizing, or politics. It gives some well-deserved attention to a largely unknown social protest movement that started with nothing but dramatically changed the participants’ lives for the better.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.