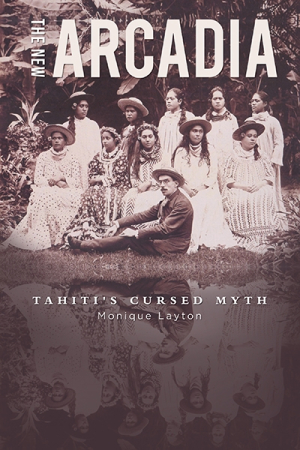

The New Arcadia

Tahiti's Cursed Myth

The New Arcadia offers a vital and compelling picture of a conflicted island and its people.

The idyllic image of a tropical paradise and the cultural costs of perpetuating that image are at the center of Monique Layton’s fascinating new book, The New Arcadia: Tahiti’s Cursed Myth. A cultural anthropologist by trade, Layton draws on an impressive range of historical material to present an unfamiliar and troubling picture of the famed South Pacific island of Tahiti. She penetrates Tahiti’s tourist veneer and reveals a native culture struggling to find its identity in a post-colonial world.

The New Arcadia is not a comprehensive ethnography, Layton admits. Although she has visited Tahiti, she has not performed extensive field work there as an anthropologist. “Unable to witness Tahitian life as an ethnographer, I needed to rely on Tahitian ‘fiction’ to review what constitutes appropriate behavior,” she writes. Thus, The New Arcadia serves as an academic history and literary and social critique. The book is divided into three sections: “The Myth-Makers,” “Ruination,” and “From Otaheite to the New Tahiti.”

Layton traces the myth of Tahiti as an exotic, leisurely, and amorous Eden back to the personal writings and records of European explorers, sailors, naturalists, artists, missionaries, whalers, and traders. She incisively, and convincingly, demonstrates how the eighteenth-century idea of the “noble savage” was a nostalgic projection rooted in a desire for lost innocence and naïveté: “The eighteenth-century Europeans did not have to look far to find the embodiment of both their longing and their wish fulfillment in the reports they read about Tahiti.” Although such romanticism was at odds with Christian missionaries in Tahiti, no European power recognized the island’s culture in and of itself. Layton clearly shows how its people and customs were appropriated by better-armed, self-serving imperialist nations.

The book’s thorough deconstruction of the Tahitian myth can be long-winded and tangential. For instance, Mutiny on the Bounty and other Hollywood films that have contributed to the Tahitian myth are summarized at length. The television show The Bachelorette, which staged a past finale in Bora Bora, also gets a mention. While the book certainly makes a case for the relevance of these contemporary idealizations of the South Pacific, the points could be presented more concisely.

From the grind of this preliminary critical work, however, a sobering perspective on modern-day Tahiti emerges. The last third of the book relates Tahitian politics, the people’s desire to be independent from France, the latter’s nuclear testing near the island, and the cultural predicament of a tourist-based economy. “There is usually little infringing of real life into those heavenly touristic spots,” Layton writes. She argues that Tahitians need the exotic myth to serve their tourist industry; yet many want to preserve their culture independent of any colonial design.

To support this modern perspective, Layton relies on Tahitian writers and the emergence of what she calls a “literature of resentment,” most apparent in female characters who take exception to being objects of sexual fantasy. “I do not want to be a myth,” writes indigenous author Chantal Spitz. This literary approach limits the scope of the book to cultural critique rather than a first-hand account of Tahitian life. Despite this limitation, The New Arcadia offers a vital and compelling picture of a conflicted island and its people.

Reviewed by

Scott Neuffer

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.