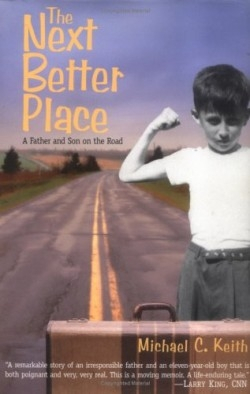

The Next Better Place

Norman Mailer once wrote about the “nobility” of the baser forms of speech. The author, in this engaging memoir of wanderlust, demonstrates how it works: “Before the sun reaches the horizon it is absorbed by a thick brown haze that I notice has been reaching higher in the Western sky each day. When I mention this, my father comments that it’s a good thing we’re heading east because it looks like the entire West is turning into a big wall of shit.”

Keith, an expert in broadcast media who teaches at Boston College and has written two books on the subject, now changes genres to tell the story of his unconventional childhood. He writes in the present tense, in the voice of an eleven-year-old boy. It is 1959, and the boy skips out on his mother and sisters and takes to the road with his father, an intermittent drunk who habitually blames others for his failings.

As the two wander across the country and back, the boy meets a cast of characters as odd and varied as life itself: two older boys who sexually torment him, a fat man who eats himself to death, a kindly but oblivious boarding house madam, a preacher easily manipulated by an insincere avowal of faith, a basement alchemist trying to get rich by mixing common household products, an undertaker whose partner rapes a corpse, and many others. The undertaker aside, he comes across a catalog of sexual peccadilloes, which he notes with something approaching indifference. He is eleven, after all.

Like many road tales, the essential story is not about life on the road but the relationship between the traveling companions. If the father is irresponsible in the conventional sense, his son has no expectation of a conventional father. He notes with neither scorn nor shame the way the tale of his father’s “war injury” changes with each telling. The thing that does bother the boy about his traveling companion is when he delays their travels by being too easily discouraged when hitchhiking through the desert or by drinking up all the money. When his father returns drunk to their boarding house in Indianapolis, the son regales him with as much scorn as he can muster: “I do not want to go anywhere with him, I say. What I want to do is go back and live with my mother. She is right about him, I continue. He is a drunken, lousy bum. A son of a bitch!”

Still, they have a bond. However unsentimental, however dysfunctional, it is strong bond and one of love.

Reviewed by

Rich Wertz

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.