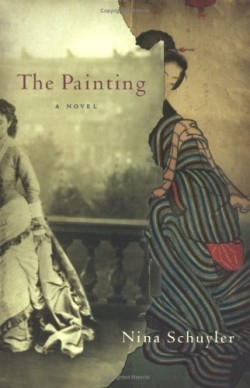

The Painting

The year is 1870. The backdrops are the Franco-Prussian War and the nascent Westernization of Japan. These worlds are linked by a piece of paper used to wrap a handmade Japanese ceramic bowl exported to France; the wrapping is actually an exquisite painting of two Japanese lovers, a painting that changes the life of the man who discovers it. This debut novel depicts two sets of characters, one in Paris, the other outside Tokyo, including soul mates and kindred spirits who never meet face to face.

After taking over the conscription of a wealthy Frenchman for pay, Jorgen loses his leg in the war. A woman, Natalia, takes pity on him while he recuperates in a Parisian hospital; she lands him a job as a clerk in her brother’s import business. Jorgen has his demons (he has run away from home in Denmark after impregnating a young girl), which are oddly parallel with the demons of the painting’s creator, Ayoshi.

In Japan, Ayoshi languishes in her arranged marriage. Her benign, ceramicist husband calls upon her daily to rub his feet, which were ruined in a house fire when he was a child. In order to escape what her life has become, Ayoshi takes refuge in her studio, painting image after image of her long-lost lover and herself. This act keeps her alive. Instead of displaying the paintings, she wraps them around her husband’s bowls before they are shipped to Europe. No one is supposed to see them, but Jorgen chances upon one. He becomes obsessed with the painting and with what it means to him, to his own lost love, and to his new feelings for kindly Natalia.

The author holds an MFA from San Francisco State University and teaches writing at the Academy of Art College. She makes an effort in this book to keep the elocution and customs of the time intact, although there are a few slips—for example, when Jorgen succumbs to the temptations of a prostitute, the woman unzips his trousers, which, in 1870, could not have occurred since the zipper was not invented for another twenty years.

Also, on occasion, the dialogue is a bit modern, but readers can forgive this, especially because the author’s love of unusual, imagery-rich language is so evident: Ayoshi’s “mind skips across the blues, like a flat stone on water. A brush made from the tail of her father’s horse dips into a pool of bruise blue and prances across the white sheet of paper.” Schuyler uses words like paint, floating them across the page, creating a mesmerizing universe.

Reviewed by

Olivia Boler

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.