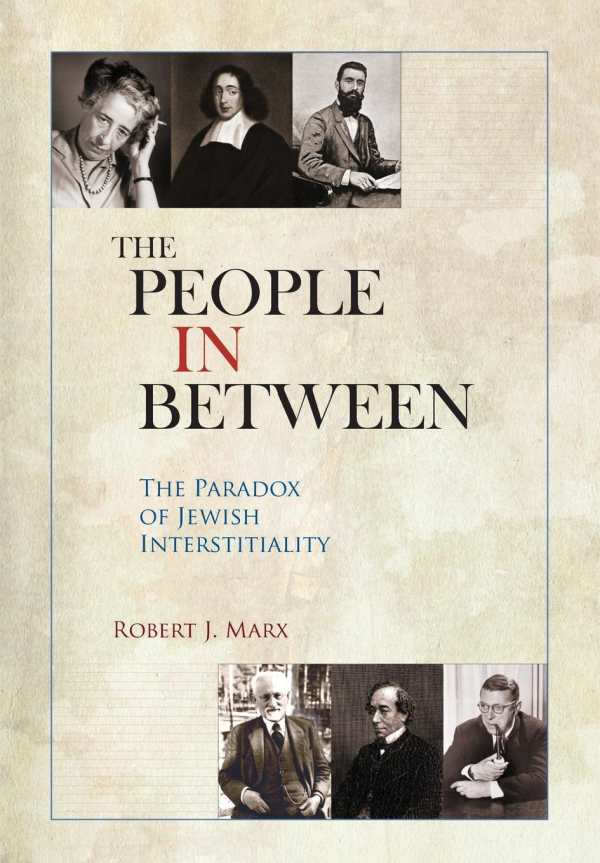

The People in Between

The Paradox of Jewish Interstitiality

Rabbi Robert Marx presents an intricate picture of the variety of Jewish identities and addresses the question of what Judaism becomes without the challenge of social marginalization.

Rabbi Robert Marx, founder of Chicago’s Jewish Council on Urban Affairs, presents a historically attuned exploration of the intermediate spaces that Jewish communities have been made to occupy down through the ages. The People in Between is a thoughtful and provocative project that follows the changing faces of antisemitism and Jewish responses to it.

Marx’s project begins with a kind of philosophical etymology: what does “Jewishness” entail, and from whence did it arise? Biblical roots are married to theological and cultural evolutions, with the author showing that Jewish communities have always found ways to adapt to the needs of the world around them. Interstitiality, or the occupation of the spaces between social norms, is presented as the historical constant. This, Marx says, is the “inheritance of a people estranged from power,” who are restricted to liminal yet visible spaces by mere virtue of perceived differences. This notion is compellingly argued throughout.

To show how Jews have dealt with the problem of their powerlessness, Marx presents individual Jews in their historical place, addressing figures from Maimonides to Hannah Arendt, from Herzl to Henry Kissinger. Such chapters explore how Jewish identity evolved to meet the challenges of distrustful neighbors, highlighting the creativity and dynamism of Jewish thinkers, even beneath the burdens of prejudice.

Responses to continual Jewish vulnerability are shown to be be communal and worldly, both considerate of the needs of Jews and of the necessity of Jewish engagement with the gentile world. In a latter chapter, Spinoza is presented as a possible model for theological creativity.

Chapters are diverse and could well be used independently of one another in Jewish survey courses. Chapters devoted to Judaism in America, where challenges still exist, if of a less insidious nature, bring tension between identity and marginalization into relief. Marx asks some difficult questions: why should Judaism survive, as what, and for whom?

In their grandiosity, some assertions will leave readers wanting more. Marx’s call to the pursuit of justice is invigorating, but the program is left unarticulated. Stances toward Israel are given scant space, and the violence of the 20th century is viewed mostly through the responses of survivors. Nevertheless, the work is stimulating and revelatory, certain to evoke empathy and increase understanding, both within Jewish communities and outside of them.

Reviewed by

Michelle Anne Schingler

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.