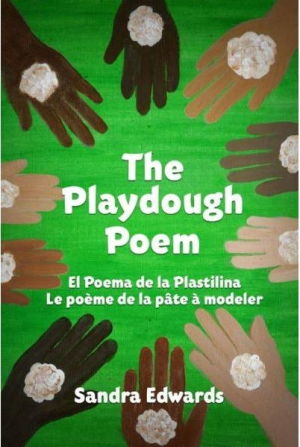

The Playdough Poem

El Poema de la Plastilina, Le Poeme de la Pate A Modeler

Playdough acts as an antievolution allegory in this lively, trilingual poem paired with vibrant illustrations.

Former Sunday school teacher Sandra Edwards delivers a trilingual poetic project designed to persuade children toward belief in creationism. The book is colorfully and playfully illustrated, but it exaggerates tensions between religion and science.

An end-rhyming, jaunty arrangement, Edwards’s poem attempts to connect humanity’s diversity and wide range of abilities to the assertion that nothing before our eyes could have come to be without God’s design. Edwards does this first in English and then in Spanish and French translations of the poem as well, each making use of the same graphics.

Vibrant illustrations full of smiling faces from across the cultural spectrum recall projects like Same, Same but Different, by Jenny Sue Kostecki-Shaw and help to infuse Edwards’s book with a youthful sense of wonder. A lump of playdough held in the speaker’s hand becomes the trope through which the creationism argument operates.

“The playdough didn’t get here by evolving from something else,” a reflection children will have no trouble absorbing, though the follow-up line, “And it won’t transform into anything in a million years all by itself” is less easily swallowed.

This argument is moved past quickly, switching focus to the human hands acting upon the clay, marveling at their formation and maintaining that each hand is the complex product of the work of God: “Muscles connect it to my arm, nerves connect it to my brain, / I can write and squeeze and hold, caress a baby, draw a plane.”

The book claims that the squeezed lump of playdough will make one see that “living creatures can’t just happen, ecosystems don’t appear: / There must be some Designer who allows us to be here.” That must, in the poem’s view, prove that evolution is a fallacy. This argument is delivered in a peppy, rhyming format, the lines of which hold wonder for God’s works and suspicion of anything perceived to undermine assigning God credit.

Edwards’s project presumes that those who argue for evolution are simultaneously arguing that “there is no God,” despite the breadth of religious institutions and the diversity of belief among scientists. The metaphor of the clay may work well as an argument for inertia, but it never quite connects to, or dismantles, ideas of complex biological development.

Those answering questions for young children in conservative denominations may find that this poem serves as a satisfactory response, and that its mostly lighthearted poetic format appeals to a young audience. Ultimately, its arguments won’t withstand greater scrutiny or provide answers to follow-up hows and whys. Conciliatory arguments between religion and evolution exist, though the project does not reflect them.

The Playdough Poem exhibits awe for humanity’s intricacies, and it is a good resting place for those raising young children in literalistic faiths. But it may prove a limited response for inquisitive minds.

Reviewed by

Michelle Anne Schingler

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.