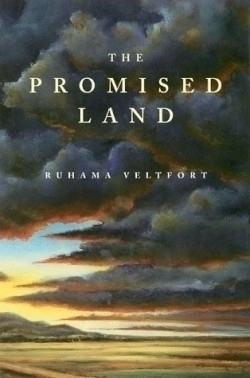

The Promised Land

In catalog copy author Larry Watson (Montana 1948) calls The Promised Land “an important contribution to the tradition of immigrant literature,” which is certainly true, though Veltfort has gone beyond following tradition here and instead has created what many in the book business have hoped for but thought impossible: a novel true to both literary and spiritual traditions.

Veltfort’s characters struggle with their relationship to each other, to history and to God, as they seek their promised land—a place they can, at last, call their own true physical and spiritual home. Some ordinary place where they won’t be persecuted for their religious beliefs, where family traditions matter but connections don’t, where human potential can be realized. This need for a home is so great it becomes the force that drives both Yitzhak, the runaway son of a powerful orthodox rabbi, and his wife Chana, an orphan just reaching adulthood, on their grand and dramatic adventure. After Yitzhak has intensifying apocalyptic nightmares, the couple flee 1840s Poland with a raggedy band of followers, and emigrate to America. There Veltfort’s skill for combining historical detail with emotional power is at once enchanting and devastating. Her beautiful yet simplistic language tells a brutal story, and her ability to present horrifying detail plainly allows both the characters and the reader to experience the full emotional force of loss and renewal.

The real accomplishment of the book is that every forward motion of the plot, each new character and the thrilling narrative which so casually winds its way through the two is held together by tests and triumphs of faith. Yitzhak’s intellectual nature and sense of otherworldliness contrast, with Chana’s more practical and questioning traits, and each are called to draw upon their own inner strength to endure the harsh New World. Only vary rarely does Veltfort give them easy answers, though sometimes conflict comes a bit too evenly paced. Once in the New World, some of Yitzhak’s followers embrace the secular, and turn their back on God; others become almost deadly in their righteousness, and these side struggles provide satisfying subplots.

Milkweed’s Editorial Director Sid Farrar said the manuscript itself has had a charmed passage to publication—Publisher Emilie Burchwald emerged from a closed-door marathon slush-pile reading session with it clutched tight and held high above her head, insisting he read it immediately. Originally an unsolicited manuscript, The Promised Land is Milkweed’s lead title for fall.

“I’m tempted to use all these clichés like ‘sweeping’ and ‘epic’ and ‘universal truths’ when I talk about this book,” said Farrar. “They might be cliches, but they all apply, in the very best interpretation of the words.”

Indeed they do, and one prone to gushing would not hesitate to add “saga” and “triumph” to his terms, and say them with a straight face.

With The Promised Land, Veltfort has created her own new version of the great American novel—one that gives importance to both spiritual and literary satisfaction, and proves that “spiritual literature” is not necessarily a contradiction in terms.

Reviewed by

Mardi Link

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.