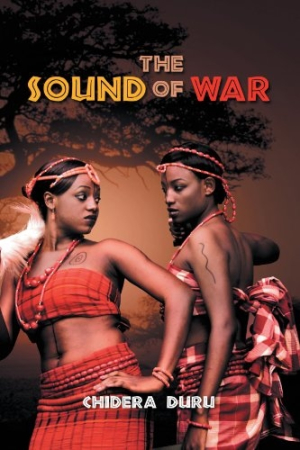

The Sound of War

“What an elder sees sitting, a young man wouldn’t see even if he climbed a tree.” This bit of wisdom from an ancient, nearly crippled, yet once legendary beauty is the core theme of twenty-year-old Nigerian Chidera Duru’s The Sound of War. Through his narrator, Chioma, the author, who is still a student, tells the story of his land and his people in the days just before the arrival of the “colorless men” of the great white queen “who now rules the whole world.”

Here is a world where warriors cover themselves in paint and clay, bear spears and shields, and fight in formalized combat on agreed upon battlefields. The Sound of War is at times a difficult read, as its timbre and meter are not meant for the ears of men “the color of water,” but instead those spawned from the very soil of Africa.

The novel opens in modern times, with a young, spoiled, London-educated prince returning to his village in the African bush, solely for the purpose of selling out his people (their land and their heritage) for the get-rich-quick scheme of a foreign oil company. It is here where Chioma comes forward to tell the story of the tribe, the village, and the statues of the ancestors that watch over them—statues the prince wants to tear down and replace with a building for the oil executives.

His story of the “Umoukwe” people is filled with tribal rituals of birth and burial, of maidens coming of age, and warriors dancing for battle. There are storytellers and schemers, warlords and witchdoctors, lovers and liars, and all manner of snakes, lions, bugs, and other terrors of the jungle, all told with color and charm and a lovely and authentic linguistic lilt.

There are errors of spelling, grammar, word use, and printing (half of chapter 18 is in bold face), but, oddly enough and in their own way, these only add to rather than detract from the novel. This is not a perfect book, and therein lies much of its appeal. If read aloud it would sound like an old village woman telling a story, and many readers will hear that voice in their heads. Duru’s book may not be for everyone, but for anyone wanting to hear the cadence and feel the pulse of an African village, it is a treasure worth more than all of the oil pooling beneath the land of the Umoukwe.

Reviewed by

Mark McLaughlin

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.