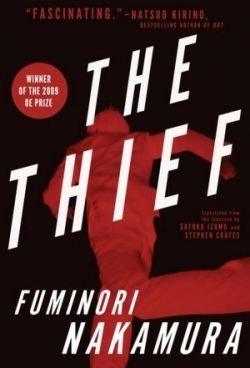

The Thief

A Tokyo pickpocket finds meaning in his otherwise drab and aimless life by reflecting on the subtleties of his art: selecting the “mark”; using a crowd to shield his motions; and extracting the wallet with a deft, fluid, two-finger snatch. Only once is the pickpocket’s name—Nishimura—mentioned, and that’s in passing. There are hints that his impoverished childhood led him into thievery. But he dwells little on his past and, for the most part, lives in the moment, with no future visualized. Because of his skills, the thief always has enough money for his modest needs. He’s basically a take-what-you-need cutpurse.

Then two transformative things happen to him: he encounters a young boy who’s learning to pilfer groceries at the behest of his prostitute mother; and he is drafted by the sadistic crime boss Kizaka to take part in a supposedly harmless home invasion to steal documents. Both events result in unforeseeable entanglements that compel Nishimura to reassess his life. He is touched by the boy’s vulnerability yet resistant to taking on the role of father or mentor. The evil Kizaka looms over him like a capricious, all-powerful god, ultimately putting his pickpocket skills to their most perilous test.

At first, Nishimura barely thinks about his own identity or ponders where circumstances have taken him. But his involvement with the boy and the gangster eventually make him confront what he has become. “I thought about my own mortality, about what I had done with my life until now. Reaching out my hands to steal, I had turned my back on everything, rejected community, rejected wholesomeness and light. I had built a wall around myself and lived by sneaking into the gaps in the darkness of life.”

Like Camus’ The Stranger, Nakamura’s The Thief is less concerned about the fallout of a particular crime than about probing the nature of human existence. The Tokyo depicted here is not a bustling, brightly lit metropolis but a dank, gray, perpetually gloomy warren of subways, alleys, and underpasses. Many of the principal characters, including the young boy and his mother, go unnamed, thereby emphasizing the bleak anonymity in which this wretched underclass lives. There are redemptive elements in the book, though, notably the loyalty of the protagonist’s best friend and his vivid memories of his long-departed mistress. The story is fast-paced, elegantly written, and rife with the symbols of inevitability.

Reviewed by

Edward Morris

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.