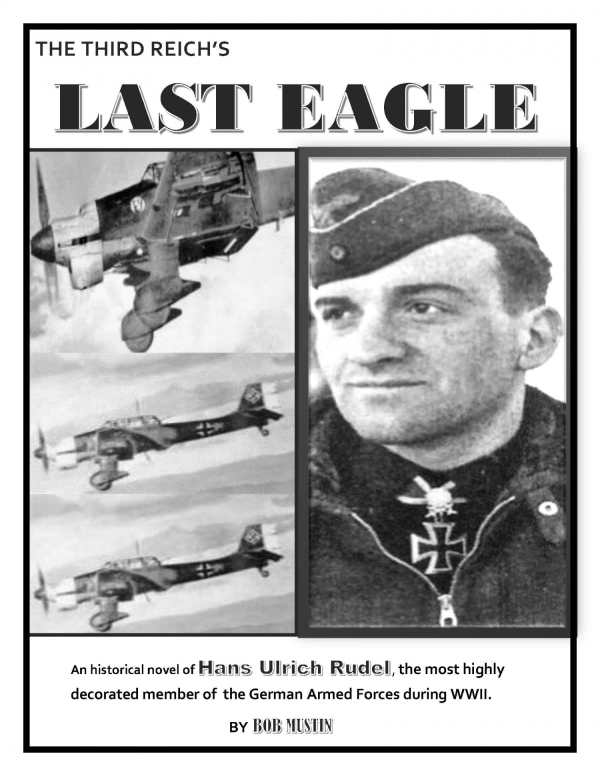

The Third Reich's Last Eagle

The book offers a convincing portrait of the daily life of fighter pilots during World War II.

Can an individual who fought for Hitler’s war machine gain the admiration and respect of those who fought against him? This is the question implicit in Bob Mustin’s The Third Reich’s Last Eagle, and the answer—at least to the Americans he ultimately surrendered to—is yes.

Billed as a “fictional biography,” the book chronicles the wartime exploits of Germany’s most decorated serviceman, Hans-Ulrich Rudel. As a gifted and determined young athlete, Rudel hoped to participate in the 1940 Olympics. When war intervened, he transferred his abilities and dedication to flying, gaining fame piloting Stukas, Germany’s much-feared dive bombers.

Rudel fought exclusively on the Eastern front, conducting bombing raids bent on destroying the equipment and military depots of Stalin’s Soviet Union.

The focus of the text is Rudel’s wartime experiences, told in chronological order. Interspersed with these are brief, snapshot-like scenes of Hitler and Stalin making the decisions that affected the lives of soldiers and civilians alike.

While these scenes lack the feeling of reality conveyed in the Rudel sections, they do expose Hitler’s flaws as a military leader who frequently and frustratingly replaced strategies already underway with whatever new plan he had come up with.

The book is at its best as a character study of Rudel and other Germans who served. Rudel is shown as a man who fought for his country, his countrymen, and a bright future for his wife and children. Since Hitler enforced wide no-fly zones over concentration camps and kept their purposes top secret, Rudel and others were unaware of them until shown pictures by Allies at the end of the war.

As a pilot, Rudel’s courage and determination never faltered. More than once he set down behind enemy lines to rescue downed pilots under his command. After losing a leg in combat, he ignored medical advice and returned to active duty with a makeshift prosthetic limb. Ordered to retire after completing one thousand missions, he returned to the air and flew four hundred more, averaging at least one and often two missions a day.

Though actual conversations with the men in his command, as well as his wife and parents, are fictionalized, the essence of Rudel’s character is bolstered by ample biographical research, and the imagined accounts blend well with verified research.

The book also offers a convincing portrait of the daily life of fighter pilots. Unlike men on the ground whose battles might go on for days or weeks, pilots’ lives involved long and almost surrealistic hours of safety on the base interspersed with high-adrenaline terror in the sky. In one particularly expressive scene, a group of pilots are discussing the likely prospect of dying in combat when one of them, finding the conversation boring, snaps on a radio and says, “Let’s dance.”

An epilogue summarizes Rudel’s postwar life but does not mention his lifelong support of the Nazi party or his political involvement in West Germany’s neo-Nazi party.

Throughout the book, the attention paid to dates, locations, and types of aircraft is detailed and admirable, though even non-buffs will find The Third Reich’s Last Eagle an enlightening glimpse at life and heroism behind enemy lines.

Reviewed by

Susan Waggoner

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.