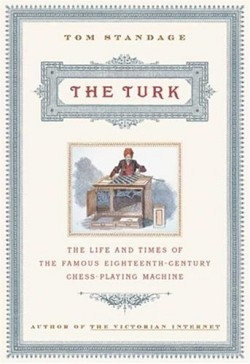

The Turk

The Life and Times of the Famous Eighteenth-Century Chess Playing Machine

When Russian master Garry Kasparov lost a chess match to the IBM computer dubbed “Deep Blue” in 1997, pessimists fretted. What would be the effect on the human psyche? The time had come when machine could out-think man—and not just any man, but one of the brainiest alive.

Not so fast, writes the author. Long before anyone had heard of computers, there was a gadget that gave some of the top chess players of its day a run for their money—and sometimes beat them. It was known as the Turk—an automaton, or mechanical man, constructed in 1770 by Wolfgang von Kempelen, a Hungarian nobleman and self-taught scientist. He dressed the Turk in the fashion of a traditional Oriental sorcerer, seated it behind a wooden cabinet, and introduced it at the court of the Austro-Hungarian empress. The Turk quickly became a sensation. Incredibly, the clockwork-powered device would study the chessboard, move its players, nod three times when placing the opposing king in check, and even correct its opponent’s illegal moves. More times than not, it won.

Kempelen built the Turk simply to prove that he could outdo a French magician who had visited the court. He soon tired of displaying it, but the machine was so popular that he ended up taking it to various European capitals, where people speculated wildly on how it worked. Some believed Kempelen controlled it with magnets or wires; others insisted a person must be concealed inside the cabinet or the automaton’s body. Questions persisted even after Kempelen died and the Turk was sold to Johann Maelzel, an inventor and showman. For eighty-five years the machine baffled and enthralled audiences in Europe and America—including, whether in fact or legend, the likes of Catherine the Great, Napoleon Bonaparte, and Edgar Allan Poe—until meeting an untimely end. Even today, although the most crucial facts are known, the debate continues about how exactly the Turk did it.

Standage, technology correspondent for The Economist, is also author of The Victorian Internet and The Neptune File. His résumé, however, should not discourage readers prone to feeling intimidated in the face of matters technological. Standage nicely blends his expertise with a journalist’s storytelling skills and painstaking research to produce a work of history that unfolds like a mystery tale. Perhaps an appropriate subtitle would be “A Technology Story that Isn’t Just for Geeks.”

Reviewed by

John Flesher

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.