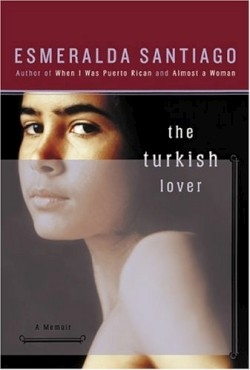

The Turkish Lover

“I gave the world a shadow of me,” writes the author, “a me who looked like me but wasn’t. I reserved the real Esmeralda in a quiet, secret place no one could reach. I kept that me so hidden I was invisible even to myself.” Santiago’s travel companion in the search for herself is Ulvi, the lover in the title, the man introduced at the conclusion of her 1998 memoir, Almost a Woman.

The co-author of two nonfiction books about Latino authors, Santiago first enticed readers with 1993’s When I Was Puerto Rican, which told of moving from her native island to Brooklyn as a thirteen-year-old with her single mother, Mami, and six younger siblings. She is perhaps best known for these memoirs, the second of which was made into a film for PBS; The Turkish Lover is a continuation of her fascinating life story.

The year is 1968 and Santiago is just twenty when she meets Ulvi, a possessive man seventeen years her senior with a secretive past and an inexplicable hold on her. She goes off with him, leaving a letter for her mother and her grandma Tata. Tracked down by Mami, she realizes years later that Ulvi wasn’t the reason she left her family: “I’d been leaving for a long time. He just provided the opportunity.”

As they travel together from New York to Texas back to the East Coast and eventually Harvard over the next seven years for educational and work endeavors, Santiago is not always certain it was such a positive opportunity. For instance, he never addresses her by her given name, but calls her Chiquita (“little one”). When she expresses an opinion, he often admonishes and placates, “Do not concern yourself.” She’s also still coming to grips with her ethnicity and what “decent Puerto Rican girls” do or do not do.

Somewhat darker than her previous memoirs, this interesting story will keep readers wanting to know what happens next. Santiago’s descriptions are rich: a co-worker in Texas is “a black-haired, hazel-eyed, peachy-skinned young woman with teeth the same brown color as Tata’s nicotine-stained fingertips.” The reader becomes well acquainted with the 1970s Esmeralda and her struggles, such as the great loss she feels when her family returns to Puerto Rico. In a sympathetically funny attempt to reconnect with her heritage, she randomly dials up Spanish names in the phone book.

Near her journey’s end with the Turk, she realizes that their relationship is “a web of matched neuroses and it was up to me to untangle them if I ever wanted to be free.” Readers are fortunate that Esmeralda chose to bring herself out from the shadows.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.