The Unknown Gulag

The Lost World of Stalin's Special Settlements

Lynne Viola, professor of history at Toronto University and a highly respected historian of the Soviet Union of the 1930s, has written a searing book on an immense and all too neglected human tragedy. It will leave no reader unshocked or unmoved.

As the 1930s opened, the Soviet government’s food production, transportation and distribution was so deficient that Stalin desperately needed to find culprits. He did so—and in blaming the already oppressed agricultural producers, particularly those in southern Russia and the Ukraine’s vast grain-producing regions, he brought about unimaginable disasters. Viola captures the blind arbitrariness of the situation. Stalin’s 1930 exhortation to “strike the kulak” (the “rich peasant grain-hoarder”) became OGPU chief Iagoda’s directive to his security police functionaries, “The kulak must be destroyed as a class.” In the ensuing years close to two million men, women, and children were deported from productive southern lands to frozen wastes in the north, the Artic, and Siberia, where climate, lack of basic necessities, and labor demands—mainly timber extraction—killed huge numbers of them. Kazakhstan, also a destination, was little better.

“Collectivization” was sacrosanct; deportations were ideologically driven; nothing about the program had a hint of practicality. No OGPU criteria defined the “rich kulak”; jealous denunciation certainly played a role in designations. Nor was the status of wives, children, and other family members considered: both the deported and the abandoned faced malnutrition, exhaustion, and death. Viola describes the settlements’ pitiful lack of buildings, supplies, work tools, and basic health facilities—rendering many too weak to be even minimally productive, highlighting the OGPU’s shattering ineptitude.

Government investigators submitted horrific reports; local governmental structures were directed to assist—and would not or could not. The deportees themselves wrote desperate letters—and these reached high-placed officials. But dying peasants and starving children elicited no human response, merely bureaucratic annoyance. Lenin’s widow Krupskaia urged Iagoda to provide aid to the children of kulaks; Pravda, she said, had rejected an article about their plight (“no facts”). Her closing statement is immensely telling: “It is clearly essential that measures be taken immediately; the issue is of immense political importance.” Yes: political importance; not humanitarian importance. Attempts were made to improve conditions: after all, the resettled had to earn their keep and produce for the Motherland. Hence selective prosecutions of delinquent administrators sporadically occurred.

Viola captures the persistent schizophrenia of the official mind. Deportees who survived to complete their terms became due for release. As this might lead to wider public knowledge of the horrors of the program, release was simply denied. Nonetheless, thousands simply “walked” through the trackless wastes of the resettlement regions and finally reached home—and talked. Ezhov, Iagoda’s successor at the OGPU (now the NKVD), ordered the re-arrest and shooting of “the most hostile [to the regime] and re-arrest and exile for the “less active, but still hostile”—with lists to be prepared within five days.

Change did come. In 1939 Beria proposed to minimally improve the settlements, offering some political rights. With the German invasion of 1941, many of the resettled became drafted into the war effort. After 1945, deportees were able to re-enter “normal” Soviet life: the terrible forced labor colonies within the state slowly died. But suppression of information about the disastrous resettlement program which killed millions and devastated grain and meat production was still the rigorously enforced policy.

Despite its magnitude and barbarity, the mass deportation of the kulaks has been largely lost to public memory, overshadowed by the dramatic Moscow trials and the Ezhov purges. The Unknown Gulag is likely to reverse this incidental amnesia, the more so as in her searing account Lynne Viola draws upon chilling documentation in Soviet archives not available to earlier historians such as Robert Conquest (his The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine was published in 1986). Viola adds a valuable dimension to her well-written account in giving the reader human voices. Desperate pleas about separated and lost families and appalling settlement conditions met with near-total indifference; official concerns about productivity and mortality rates led to exculpatory, buck-passing responses. Man’s inhumanity to man is indeed beyond imagination—and without reason.

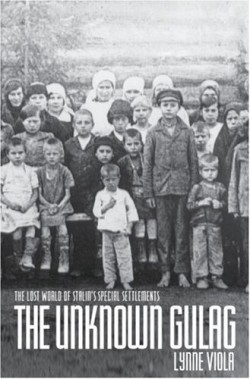

A glossary, map, and chronology map aid the reader, and the extensive bibliography cites Russian archives and books as well as English-language sources. Photographs of key players in most cases reflect a calm, detached normality; pictures of camps capture the hell they created in their catastrophic plan. How the Soviet Union recovered from colossal assaults on its key food-producers and moved on to harness and direct a labor force capable of heroic performance in World War II remains a miracle. Terrified obedience and a work-yourself-to-death ethic might be part of the answer.

Reviewed by

Peter Skinner

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.