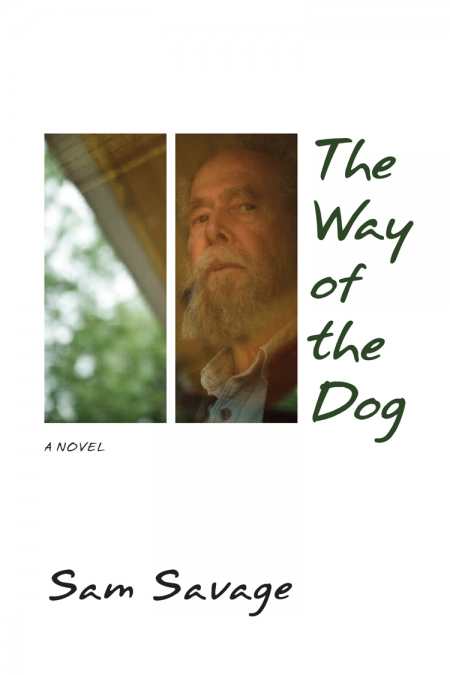

The Way of the Dog

It seems safe to say that Sam Savage is a modern master of the monologue—a label that might be applied to him by one of his own characters, sarcastically, and probably in italics. Savage, who lives in Wisconsin, is also a national treasure who is, ironically, better known in Europe. This outsider status is fitting, in a way, because Savage’s output has been a consistently empathetic and humorous rendering of outsiders. In elegant, lively prose, he gives voice to the voiceless (once, literally, in Firmin, which is narrated by a well-read rat), and the marginalized.

Harold Nivenson, the narrator of The Way of the Dog, is the most depressed and misanthropic, as well as the most critical and philosophical, of Savage’s creations to date. “I don’t understand how anyone can listen to the radio for even fifteen minutes and not want to kill himself,” Harold tells us. “Radio and television, I have always thought, are just part of an ongoing mental-annihilation and self-suffocation process that is crushing me and everyone like me.”

So, Harold, umm—read any good books lately? One shudders to imagine having to while away an afternoon with this old grouch in his dilapidated house (which he rarely leaves), as his son and his son’s family are obligated to do, but it’s fun to be complicit in a private rant against the public ranting that we sometimes find ourselves subjected to, and Harold companionably qualifies the above quotation with, “By people like me, of course, I mean the ones generally regarded as inveterate gripers.”

The story of Harold’s past comes to us piecemeal among anecdotes about his present, musings about art, and descriptions of the people who populate his life and thoughts. Chief among these is his former hero and nemesis, a successful painter named Peter Meninger, who lived and worked in Harold’s large house, which was the site of a bohemian artists’ commune when they were both young men. Peter has long since moved on, and Harold rails against Peter’s paintings, which still hang on the walls and are now worth a lot of money. He also rails against the unconscionable gentrification of his neighborhood. The infiltrators he observes from behind his windows include a novelist/professor (“Obviously she is using some kind of trick, you can’t write that many novels unless you have a trick”) and a couple of cyclists (“the spandexed giraffes”).

Having tried his hand, without pushing it very hard, at painting and at criticism, Harold’s most incisive critiques are of himself. As he tells us, “I could have been a successful minor artist, but instead I was a failure as a major artist. I was a concealed failure as a major artist. By concealing the artist I was able to conceal the failure.” This is a sad, painful way to live, and to have the courage to admit that this is what one has done is comparable to having Savage’s courage to present such a piercing portrait of the dilettante as an old man.

Reviewed by

Justin Courter

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.