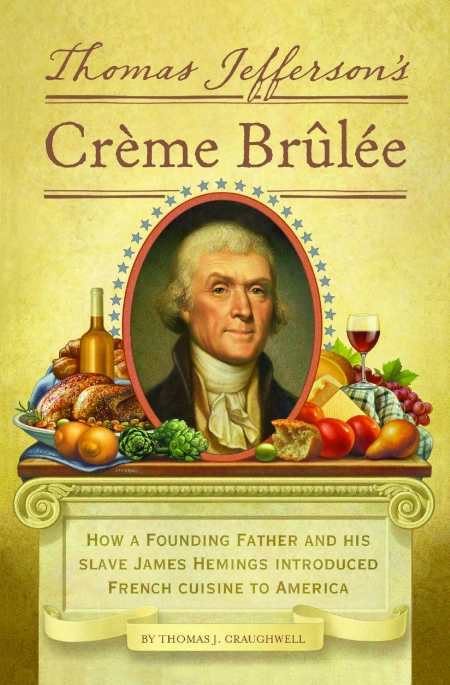

Thomas Jefferson's Crème Brûlée

How a Founding Father and His Slave James Hemings Introduced French Cuisine to America

In Thomas Jefferson’s Crème Brûlée: How a Founding Father and His Slave James Hemings Introduced French Cuisine to America, author Thomas J. Craughwell serves up a lively story with a generous helping of culinary history.

Political rivals often used Jefferson’s Francophile tendencies against him (case in point: he was once condemned for having “abjured his native victuals”) but, as Craughwell points out, for Jefferson, improvement was an essential ingredient of the American spirit. He “loved what was native to America—Indian corn, Virginia ham, representative government—but he knew there was more to be had.” And so, during his diplomatic assignment to the French court, Jefferson took note of everything he enjoyed with the express purpose of improving life in America when he returned home.

Thomas Jefferson’s Creme Brulee is a charming book that will appeal to both foodies and lay readers. Die-hard history buffs, however, might be disappointed that it doesn’t tackle the more famous connection between Jefferson and the Hemings family—namely, his relationship with Sally Hemings. Readers familiar with that story may find it strange that the relationship isn’t touched upon more here, particularly when Sally Hemings herself shows up in France chaperoning Jefferson’s daughter. But the relationship with Sally Hemings occurred outside the time period with which Craughwell is concerned, and the book’s primary intent is to explore Jefferson’s relationship with her older brother, James, about which very little has been written.

Through its anecdotes of Jefferson’s social life and James’s study of French cuisine, the book winds up providing a fascinating history of an unusual sort. Pre-revolution France is often exclusively depicted in terms of costuming and the royal court, but Craughwell instead focuses on the minutiae of French everyday life. He contrasts, for example, French kitchen construction, table setting, and food prep with the more rugged practices in America. National differences are so often depicted at the lofty level of government that it’s downright revelatory to instead confront those differences in the kitchen and at the table.

It’s also provocative to see the ways in which Jefferson imported the French traditions and conveniences—along with “crates of mustard, and nectarines, and almonds, and olive oil, not to mention the 680 bottles of wine”—incorporating them into Monticello life upon his return. As Craughwell writes: “Jefferson didn’t abandon his native victuals; he married them to those of France.” The story of how he did so is both fascinating and fun.

Reviewed by

Oline Eaton

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.