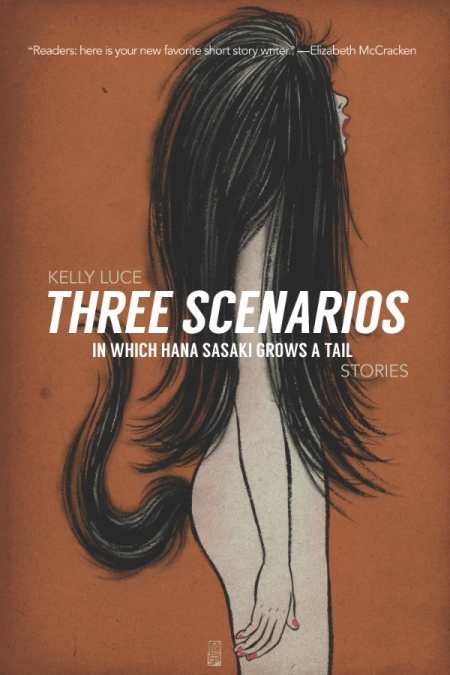

Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail

- 2013 INDIES Winner

- Editor's Choice Prize Fiction

Precise, thorough, stirring studies in character make these stories of Japanese culture a magical experience.

Traversing the profound with a delicate, often humorous voice, Kelly Luce uses the setting of Japan in her short story collection, Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail, to analyze loss, marriage, and pervasive hopes. Her precise and stirring use of language makes this an extraordinary debut.

Each of the characters in these ten stories—some cynical, some compassionate, some dissociated—shares an experience that was life-altering in some way. Several stories are narrated from a future point of view, providing the speaker with a sense of quiet insight into their experience while remaining detached from any trauma or otherwise difficult emotions.

In “Ash,” for instance, an American ex-pat details her encounter with the Japanese legal system, bringing in symbolism when she mentions the volcanic ash that covered the city like dust on the day of her arrest. This odd tone of nostalgia and the selectivity of memory is also present in “Cram Island,” as a man remembers his high school girlfriend’s best friend and wonders what happened to her after a haunting experience they shared. “Ms. Yamada’s Toaster,” too, deals with the effects of time, as the young narrator helps Ms. Yamada destroy her toaster, which prophesizes peoples’ deaths. Luce evocatively uses symbolism and imagery as she describes how the woman baptizes the toaster and herself in beer to wash away original sin and make them pure.

The stories feel connected even as they vary thematically. The characters in each story come from different life stages and narrate diverse experiences. The thread running through this collection is the setting of Japan. Luce, having lived in the country for three years, incorporates Japanese motifs and occasional gentle humor to offer a strong sense of place.

Luce presents the main character of every story both precisely and thoroughly. For example, in “Rooey,” Luce puts the narrator’s relationship with her recently deceased younger brother, Rooey, in a clear light. First, she dreams Rooey is a shark, and only when she lets him attack does she wake up, saying, “That giving in is a release so powerful I find myself sitting up in bed, heaving. That giving in is the saddest feeling in the world.” Next, describing the jealousy she feels at Rooey getting more attention from their mother, she says, “Tearing through the water on the final leg of a race, I would think of them watching me and I would for a moment be the focus; I would fill that tiny space between them.” And third, Rooey gets a job and works hard to earn enough money to buy his first car, while the narrator had gotten a hand-me-down when she was his age, to which she confesses, “He was a hard kid to resent, and for that, I have to admit, I resented him even more.” These scenes paint a picture not only of Rooey and the narrator but also their relationship, a tricky task that Luce accomplishes with skill and eloquence through her exact word choice. In so few words, Luce says so much.

Those interested in Japanese culture, or who simply wish to enjoy a magical exploration of memory and motivation, will delight in this eloquent book of short stories.

Reviewed by

Aimee Jodoin