Through the Eye of My Lens

A visit to the website of photographer Joseph B. Hendrix can result in some serious procrastination as one begins to explore the rich color images of European castles, lakeside villages, military sites, royal palaces, and other architectural gems. And yet Hendrix’s book of black-and-white photos, Through the Eye of My Lens, is a letdown by comparison.

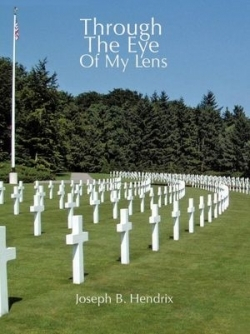

The majority of the eighty-four images chosen for these pages—while they suggest interesting settings, stunning views, imposing architecture, and intriguing design—mostly fall flat. The book’s slightly haunting cover photo, which depicts curving rows of crosses at an American military cemetery on European soil, holds out promise that inside a reader might find a collection of thoughtfully composed works. Unfortunately, there are only a few. Overall, the photographs tend toward unimaginative compositions. Most of the subject buildings are centered in the frame, and shadows often obscure detail. For these centuries-old, grandly designed buildings, we see little drama on the page.

The book is further hampered by a seemingly haphazard organizational flow, hopscotching between thirteen different countries and seesawing from castles to churches, palaces to châteaus, townscapes to mountaintops, forts to cemeteries, monuments to lakeshores. The overall feeling is less a singular photographer’s vision and more a 1970s slideshow of Uncle Charlie’s grand tour.

Hendrix’s image descriptions are also problematic. The text is often poorly punctuated, roughly organized, grammatically incorrect, and blandly repetitive. Yet when he shifts from merely listing historical points into a more personal narrative, describing why and how he made the photo, his prose is instantly more interesting, and the value of the image is increased. Likewise, Hendrix’s photographs are largely devoid of humans or animals—this is intentional, according to his introductory note—and yet those that do feature living beings are much more engaging, both from technical and emotional viewpoints.

An additional impediment to the book’s credibility are at least ten images that do not appear to be wholly photographic, but perhaps overlaid with pen or brush strokes. Without explanation, a reader is confused at best, suspicious at worst. A few otherwise benign photos are described (in a black-and-white book) as “colorful,” leaving the reader feeling slightly cheated. Part of the problem is perhaps not Hendrix’s fault, but was more likely caused by the inferior printing capabilities of the self-publishing house.

The collection is not without merit, however. Hendrix, an Air Force veteran and reservist, exhibits deep respect for American military sites, and his photographs of the cemeteries, battlegrounds, and monuments of World War II can properly still a reader. A handful of river- and lakeside village scenes, especially those with classically timbered buildings, draw the audience in. The more unusual of his images also intrigue—cave entrances as grand as castle gates, crows resting on a mountaintop railing, imposing reflections of grand buildings in lakes and moats, an oddly shuttered window.

Occasionally, there is a completely unexpected and riveting image, along with some fascinating lore, tucked into Hendrix’s text. Unfortunately, such surprising treats are found on only a few pages of this collection.

Reviewed by

Lisa Romeo

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.