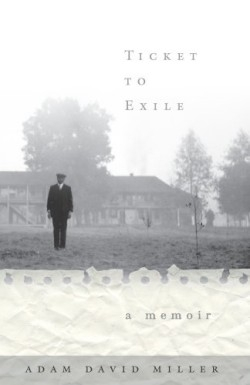

Ticket to Exile

A Memoir

“I would like to get to know you better,” read the carefully typed note Miller surreptitiously—or so he thought—slipped to a young, white dime store cashier. Certainly, he knew that interracial dating was forbidden. In this three-part memoir, Miller describes select events in his life that led to his “crime.”

It was Orangeburg, South Carolina, in the early 1940s when “public meant white.” Schools for blacks were inferior; black teachers were so severely underpaid they had to work in “service” to supplement their income. White youth enjoyed a public swimming pool while blacks swam in a channel without a lifeguard. Whites were granted priority when surplus food was distributed, and white farmers took advantage of loans from the government. Miller might have stayed in South Carolina and found ways to challenge racism had he not been released from jail with the understanding that he must travel north and enlist in the U.S. Navy.

Miller’s descriptions of escapades about town during childhood suggest threads of an adventure while the picture he paints of destitution, illiteracy, and the injustices suffered by those trying to survive the depression reveal tragedy. A poet and dramatist, the author’s use of idioms is rich and authentic, placing the reader firmly in the south: “My sisters got a dressing down from Mama;” “Mr. Charlie Summers… came to my rescue after a fashion;” and “We had a tough row to hoe….”

Despite occasional lapses related to time sequencing and redundancy, excerpts of this book would make an informative read-aloud for teaching about the Depression, southern writers, or critical race theory. Some might find Miller’s use of prose speckled with free verse poetry an effective device worth mentioning in a writing class. It is surprising, though, that Miller does not seem to spend as much time condemning a judicial system (and society at large) that would arrest, jail, and exile a man for passing a woman a note, as he does articulating the rejection he believes his action might evoke amongst black women. “In seeking out a white woman I had turned my back on the race, on them [black women].”

This memoir adds to an already impressive list of literary contributions, as the author offered dialogues during the Black Arts Movement and published one of the seminal poetry anthologies of the early 1970s, Dices and Black Bones: Black Voices of the Seventies. Miller concludes, “The longer a secret is kept, / the harder it is to reveal, / and the more painful to conceal.”

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.