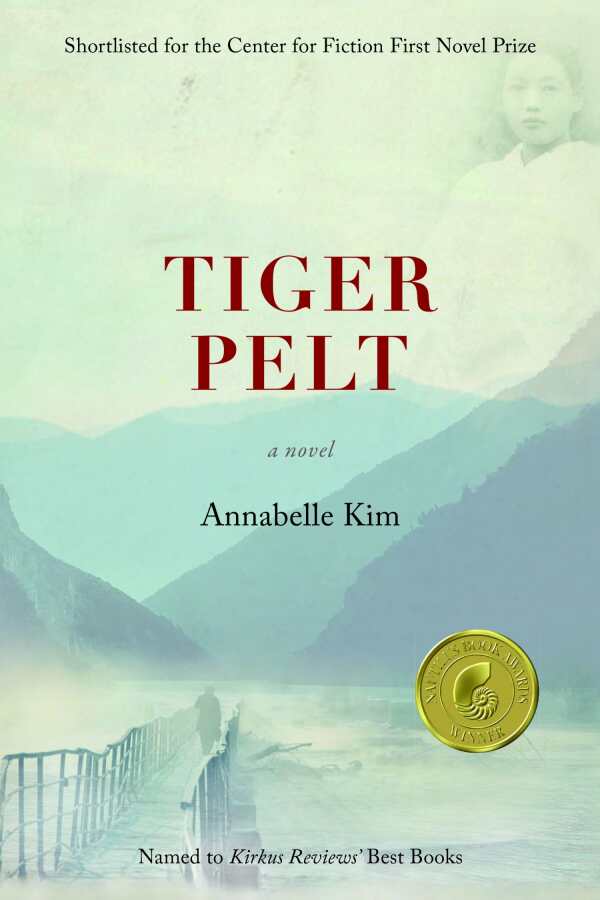

Tiger Pelt

- 2017 INDIES Finalist

- Finalist, Historical (Adult Fiction)

Intelligent, polished, and thoroughly readable, Tiger Pelt is a story of deprivations and human endurance that is beyond heroic.

A compassionate, sensitive story of hardship and endurance, courage and triumph, Annabelle Kim’s Tiger Pelt follows two Koreans from the country’s World War II Japanese occupation through the Korean War and later reconstruction.

The tale begins as WWII rages. The Imperial Japanese Army occupies the Korean Peninsula, keeping its people in a condition near to that of slaves. Thirteen-year-old Lee Hana is conscripted as a “comfort woman.” Hana’s tale of sexual abuse is a harrowing descent from rape by Japanese army officers down to a filthy “cramped and sour stall” where she’s forced to service soldiers fifteen hours a day. After the war Hana struggles, finally resorting to prostitution. Later, she marries a kind African American soldier and immigrates to the United States. Sadly, she cannot integrate into American culture and her husband divorces her.

Kim Young Nam is luckier. He avoids conscription. In a family of Christian converts, he’s caretaker of his younger brother Owlet, a child of special promise. Despite meager circumstances, the family honors scholarship above all, but in war’s chaos, Young Nam cannot attend school. Later, during the Korean War, forced into refugee status by invading communists, Nam works with the US Army. When the war is over, he follows an older brother to Seoul where he finally attends college. He later immigrates to America but returns decades later.

Despite the reach of the narrative, the pace remains steady even as it pauses for insights into Korean culture. As an example, Young Nam’s oldest brother is forced to find work in Seoul, leaving his inheritance as the firstborn son. Hana, tainted by her war experience, settles for a bad marriage. In her mother-in-law’s house, she’s relegated to the hardest work because she is the newest daughter-in-law and is later cast out.

The brutal inhumanities of the Japanese make for difficult reading, yet there are also anecdotes of compassion and generosity. The emotional power of the two stories lies in the depiction of the characters’ stoic endurance, ambition, and hard work.

In this novel of character, the conflict is both internal and external, something that is further emphasized after Young Nam and Hana meet in the United States. They both inspire empathy, but there is also a disconnect. It’s almost as if the hell the two endured is too remote from our everyday world. Also depicted are everyday details of Korean life in war and as the nation rebuilds.

The setting, whether conveyed through a glimpse of Korean mountains or via the frigid, intense cold of Manchurian winters, is telling. As the narrative shifts to the United States, characters glimpse the wealth of San Francisco and the segregated suburbs outside of Washington, DC, providing an interesting contrast.

While there’s an occasional odd metaphor or analogy, the book easily shifts from Young Nam’s to Hana’s story, with a mood that is sometimes stoic, sometimes passionate and intense, but with a solid grip on storytelling.

Intelligent, polished, and thoroughly readable, Tiger Pelt is a story of deprivations and human endurance that is beyond heroic, yet entirely believable.

Reviewed by

Gary Presley

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.