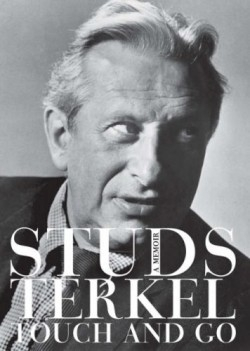

Touch and Go

A Memoir

“I have been an eclectic jockey; a radio soap opera gangster; a sports and political commentator; a jazz critic; a pioneer in TV Chicago style; an oral historian and a gadfly,” Terkel writes. At age ninety-five, Studs Terkel can double-check autobiographer on his CV, for the title was originally earned in 1979 with the publication of Talking to Myself: A Memoir of My Times.

Touch and Go is not chronological, rather it’s a gathering of poignant anecdotes, which, like Terkel himself, march to their own drummer. Having spent seven decades perfecting the craft of interviewing others, he still writes with the same clarity, humor, and brevity that have won him international fame.

The author was born in 1912, three weeks after the Titanic sank, and moved to Chicago in 1921, where his parents first owned a boarding house and later operated the Wells-Grand Hotel. The boarding house and hotel denizens were nursing students, laborers, and the occasional hooker. These were among the types of ordinary citizens that filled the pages of Terkel’s books, people whom the author calls “the etceteras of history.” He credits them with inspiring his activism and providing him with his education in life.

During the Depression, Terkel’s activism and progressivism were forged in Roosevelt’s New Deal. His ideals remain undiminished over the years, but the price he paid for them included a thick FBI file and blacklisting during the McCarthy era. Terkel is at his funniest when he recounts a phone conversation with an FBI agent, which he mistook for a crank call. In 1934, the author received his law degree from the University of Chicago, but by this time acting, not the law, was his passion. While appearing in the play, Waiting for Lefty, he received the nickname Studs because of his fondness for James Farrell’s Studs Lonigan novels.

Billie Holiday sang at Terkel’s World War II sendoff party. He and his wife, Ida, were pioneer civil rights supporters and Terkel acknowledges that his greatest honors were his election to the Lesbian and Gay Hall of Fame of Writers—he is possibly the only heterosexual so honored—and his appointment to the Hall of Fame of Black Writers. Some of the more memorable stories are racially charged: his wife Ida telling a famous journalist “to f\\\ off!“ when he let slip a racial epithet, or when civil rights advocate Virginia Durr called Senator James Eastland, a 300 pound bigot, “as common as pig tracks.“ Terkel also tells of Bill Dawson, the African-American leader of Chicago’s First District, who would deliver the black Democratic vote as decisively as Mayor Richard Daley would deliver the white ones.

Among the most entertaining stories are those that tell about Terkel’s work as a radio celebrity and TV pioneer. “The Wax Museum,” which began airing in 1944, allowed Studs to spin his favorite folk, jazz, blues, and opera, and was the forerunner of the underground FM radio shows of the late 1960s. His TV show, Studs’ Place, won him a large Chicago following, but was pulled from the air in 1951, after only two years, because the sponsors bailed on the unfounded rumor that Terkel was a Communist Party sympathizer. The next year, Terkel began a forty-five-year relationship with WFMT Radio that broadcast the Studs Terkel Show, which became home for his on-air interviews.

The book’s final section, “Truth to Power,” is a reverent tribute to people who have stood up against the oppression of their times. These include vignettes about the author’s journalist friend James Cameron, peace activist David Dellinger, and scientist and anti-nuclear bomb activist Albert Einstein.

Terkel concludes with a look back and a look ahead, which come with a warning that only a ninety-five-year-old keen observer of the human condition is likely to offer. He fears the spread of a “national Alzheimer’s” in which the country forgets its past. As pictures of Paris Hilton dominate the media and the government refuses to allow TV images of caskets returning from Iraq, Terkel, as he has always done, places his faith in “history’s etceteras” to correct these wrongs. [i]

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.