True Nature

Cathartic, unpretentious memoir details the author’s journey through addiction and OCD with a tone of conflict and compassion.

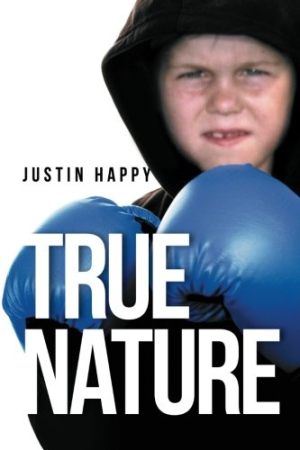

True Nature, Justin Happy’s story of trauma and the road to healing, starts when the author begins boxing lessons at age seven. He was often bullied by his older brother, so his mother suggested it as a confidence builder. He soon quit because as he excelled, he couldn’t stomach hitting weaker opponents; it reminded him of his own helplessness.

This brief, three-paragraph opening sets a tone of conflict and compassion for the rest of the book. From boxing, the author turned to theft as a release. By high school (and by page three of the book), the author is in trouble with the police and has a drinking problem.

The back panel copy tells readers that this will be a story of life transformation, but readers won’t yet have a clear picture of the exact issues the author deals with. It mentions brotherly love, but it’s unclear from the back cover exactly how that concept plays into the author’s life.

The book is divided into two parts. The first, which seems to be the “True Nature” mentioned on the cover and title pages, is a short account of the author’s life. The second part, titled “Book Two: Brotherly Love,” traces the effects of addiction (to smoking and alcohol) and obsessive-compulsive disorder. There is no table of contents to help readers discern the purposes and contexts of the two parts of the book.

Within each part there are very short sections, from several paragraphs to a page or so. Most have headings that include the year and/or place of the event, and some offer themes or topics of the section, such as “Brothers,” which keep the book from feeling too disjointed.

Many memoirs fall into the trap of over-sharing; the author finds his or her own life profoundly interesting and assumes readers will, too, resulting in a long-winded narrative. Happy has the opposite problem: his fairly intriguing life story wraps up in the first part of the book in a mere twenty-eight pages.

“Brotherly Love,” however, is a bit free-flowing and disorganized, but readers who can identify with Happy’s struggles will find comfort in his voice and encouragement in his words. In addition to sharing with people in circumstances similar to his own, Happy offers his thoughts on the economy—“The problem with the economy is there are too many people running around unconfident of themselves”—and how education can help kids who struggle with anger, addiction, and OCD, like he did.

The final paragraph of the first part of the book gives readers a sense of Happy’s clipped, utterly unpretentious style: “I haven’t drank or gambled for eight months. I go to meetings. I take my medicine. I see my son. I have a van in the driveway and an ad in the paper. Life goes on.” While his writing is not literary or artful, its raw honesty shows that writing is cathartic for the author, and even readers who don’t relate will feel the urge to examine their own life stories and seek healing.

Reviewed by

Melissa Wuske

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.