Until We Meet Again

Impassioned calls to action based on the author’s trying life experiences are embedded in a fascinating narrative.

Thomas Toren’s short but thorough memoir, Until We Meet Again, is filled with lessons learned over a lifetime. Each one reads not as a cautionary suggestion, like lessons sometimes do, but as a blessing bestowed upon the reader in Toren’s guiding tone.

A man who has lived through his own significant trials, beginning as a young boy scarred by the Holocaust and its divisive effects on his family, Toren makes beautiful observations of universal truths. For example, he makes the poignant statement that “as children, we accept everything as being normal. Only as adults, with the benefit of some acquired wisdom, are we capable of considering the past with deeper understanding and objectivity.” Toren’s work centers around his struggles to establish his identity, something to which many readers will find connection, regardless of personal background or disparate experience.

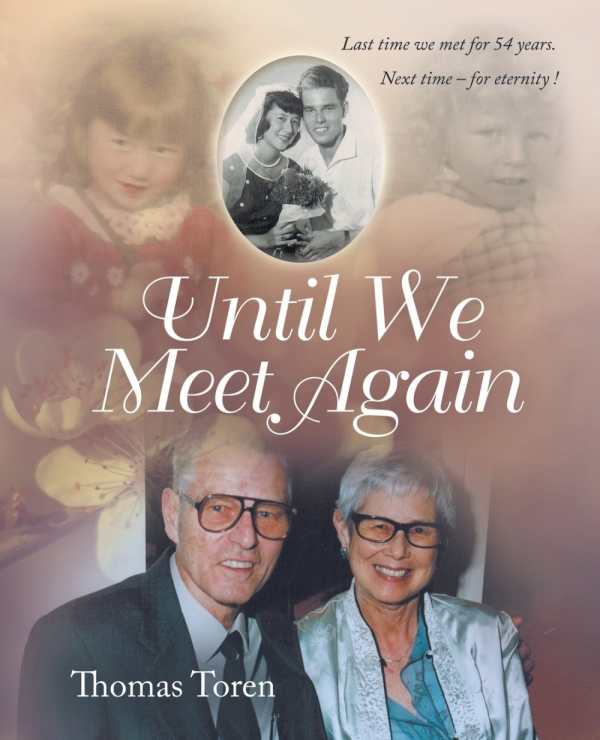

The organization of the work could benefit from some revision, but this seems to be the result of the narrative structure being overwhelmed by an enormous amount of compelling material. Often, Toren prefaces what he intends to explain rather than simply explaining it, which might be more effective for the reader. For example, some of Toren’s lessons, though well-stated, might be better left unsaid and represented by his illustrative scenes: “We should also learn to fully appreciate all of our blessings, as most of us have many that we take for granted.” This same lesson comes across much more memorably when he recalls that his wife of fifty-four years, Lisa, “told [him] that when she woke up at night, she lie in bed literally counting, visualising and enjoying all her God-given blessings!” Using well-rendered scenes and precise images in place of observations brings greater animation to Toren’s narrative and the people within, allowing a more intimate entry into his work.

Much of Toren’s narrative strikes a common chord in calls to action, specifically concerning education and legislation. These impassioned pleas are based in his experiences, first as a young boy living in the wake of mass genocide and later as an older man witnessing the loss of his beloved wife and the unnecessary suffering she endured.

The first, a call for education, is steeped in Toren’s dedicated attempt to understand in a more personal way the magnitude of the Holocaust: “Having done the cold maths of millions, I then tried to think of the individual victims, their fear and suffering for their loved ones and themselves whilst anticipating their families’ and their own inevitable demise.”

Later, he writes of Lisa’s failing health. Lisa, the woman who loved to count her blessings, “for the last four months of her life … had been asking her palliative-care doctors to expedite her death.” Her suffering was clearly overwhelming in its intensity, even for a woman with a spirit grounded in gratitude. Her eventual passing was more painful than it ought to have been, according to Toren, who insists that legislators have an obligation to address the potential for ethical euthanasia practices in palliative-care patients.

By the memoir’s conclusion, Toren has, if not uncovered, most certainly created his identity. His new ambition is to leave a written record for his grandchildren and great-grandchildren so they might understand who he is, and perhaps, with that knowledge, understand themselves a bit better.

Reviewed by

Amanda Silva

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.