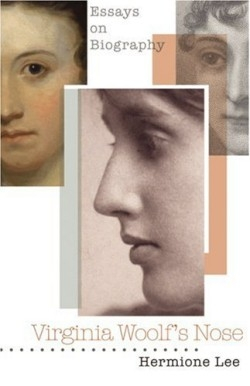

Virginia Woolf's Nose

Essays on Biography

In England (where the author enjoys higher name recognition as Oxford University’s Goldsmiths Professor of English Literature, author of biographies of Virginia Woolf and Willa Cather among others, and a Commander of the British Empire for services to literature), this genial collection of lectures on the biographer’s modest arts was aptly titled Body Parts: Essays on Life-Writing. In America (where literary merit so often defers to celebrity), its new title is Virginia Woolf’s Nose, a game jab taken on behalf of the rather patrician profile of the author of Mrs. Dalloway against the rubbery prosthetic one that helped Nicole Kidman to her Best Actress Oscar as Woolf in The Hours. It makes for a curiously uneven contest.

“Opinions change as the times change,” noted Woolf, and with them so do obsolete conventions of biography. Victorian prudery towards recording eminent lives has turned more inward and private, a sexually frank inquiry of what Joyce Carol Oates called “pathography.” Lee gracefully marks these sea-changes in essays that chart the evolution of Shelley’s and Jane Austen’s reputations: Mary Shelley jealously shielded her husband’s “irregular” love liaisons from prying biographers while bolstering the myth of how his heart was plucked from the funeral pyre; Austen’s family created such a dear “Aunt Jane” Victorian hagiography that her image is still used to advertise coach tours of Regency houses, while modern biographers read into the gaps in her correspondence dark speculations of her psychic state. Free of academic cant, and briskly told, these essays are models of conversational scholarship, all turning on the question, “where do biographers start from, and when do they know when to stop?”

The shifting styles of deathbed descriptions are the focus of Lee’s essay on “How To End It All.” Here the biographer’s scruple must weigh against second-hand testimony. From Chekhov’s death (complete with champagne and elegiac dialogue) to Freud’s (who was determined to keep his death his own, burning papers, queering future biographers), to Dickens’s last moments (in which current biographer Peter Ackroyd ushers in many of the author’s most beloved characters to share the experience), the biographer still exerts a powerful dominion: “the subject of a biography always dies in the biographer’s own way.”

All of which leads, rather ominously, to the final essay, about the Hollywood-enhanced depiction of Virginia Woolf’s suicide in The Hours, which owes less to scholarship than to cinematography. For the millions of film-goers and the far fewer readers of Lee’s own biography, a killing review: “And now the death has been simplified, or Ophelia-ised as the romantic immersion of a beautiful young woman with a very long nose in beautiful still waters, with music playing.” (Woolf was near sixty, the river muddy, the day frigid.)

Lee writes wonderfully of the necessary fictions that are hidden in the biographer’s reconstructive taxidermy. But the reader is left grasping at questions that evade her bailiwick: how do we trust any biographer, given the amount of subjective slant that she has so brilliantly documented?

Reviewed by

Leeta Taylor

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.