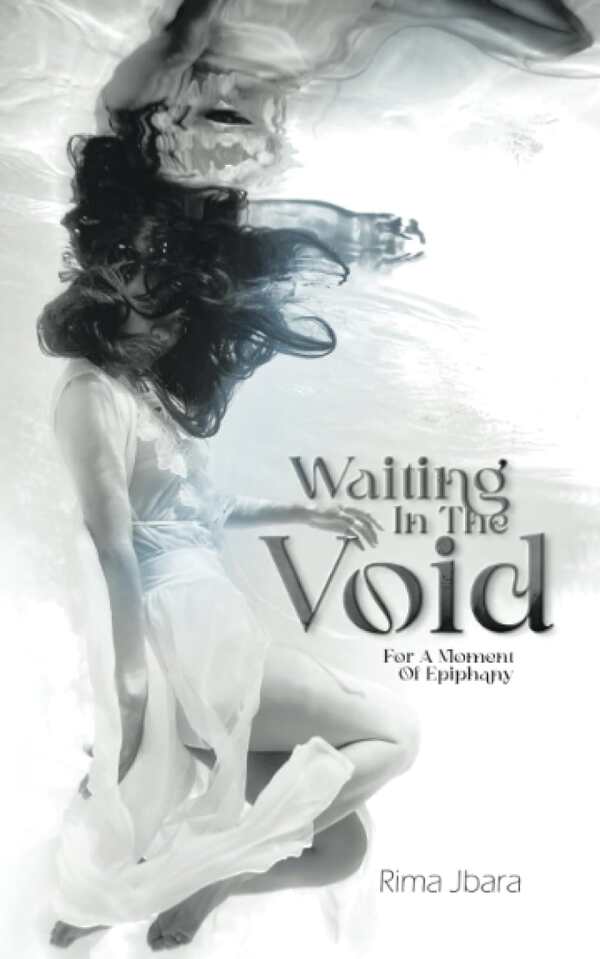

Waiting in the Void

For a Moment of Epiphany

Waiting in the Void is an ambitious experiment in hybridity and ungirdled expression, articulating a humane set of philosophical maxims.

Rima Jbara’s Waiting in the Void for a Moment of Epiphany is a diaristic hybrid book, composed equally of free-verse poems, short stories, dialogues, and epistles.

Eschewing any narrative structure, the book is organized into ten thematic sections with foci including pain, sanity, and dogs. Each section begins with a letter that addresses the theme and provides an overture for the five pieces that follow. These pieces vary in form; few exceed a single page in length. The short stories and the philosophical dialogues tend to feature two characters in direct conversation on the section theme, with one of the characters being a foil for the didactic instruction of the other. And the poems are confessional, ruminating upon injustices or physical challenges.

“Sorry, Not Sorry” deals with the abandonment of a work post; “If You Find Yourself Caught in Love” deals with the dissolution of a romantic relationship. Both pieces are representative of the collection in general; their dramas are reduced to simple moral soundbites, leaving their characters vindicated but essentially unchanged. And strange beside the book’s other themes is the anthropomorphism of dogs, to which two sections are devoted (“Dog” and “Child”—the latter being a redundant, tongue-in-cheek reference to the former). Several pieces within each of these sections hinge upon the worn oddity of a narrator or main character who treats and refers to her pet dog as a baby and expresses dismay when others refuse to do the same.

While most of the book’s characters function as mouthpieces for sociophilosophical ideas, on occasion, they are developed with more nuance. In “Tears,” two women struggle in private—one with domestic abuse, the other with a terminal diagnosis. Their brief encounter with one another on a park bench is enigmatic. And “Creature Fear” describes the experience of sleep paralysis, foregoing a single message or meaning to allow for myriad possible interpretations. Some lines, like “Some damaged her soul less, where some damages remained her shadow,” proffer syntactical delights.

Still, the book’s generally rigid moral philosophy means that it often comes across as hypocritical or dependent on straw-man premises. In “Picture to Burn,” for instance, the narrator espouses her own virtue of modesty, claiming that others recognize her status not because she boasts it, but because of her virtuous appearance and lifestyle; in the same piece, the narrator derides men for not respecting knowledgeable or opinionated women and derides women for not bothering to cultivate themselves. The entry’s dramatic irony seems unintentional; outwardly, it insists upon its moral correctness to the degree that it undermines its own authority. Further, grammatical, spelling, and punctuation errors abound.

Waiting in the Void is an ambitious experiment in hybridity and ungirdled expression. While it aims at articulating an earnest and humane set of philosophical maxims, it falls short for its unchecked didacticism.

Reviewed by

Anthony Hamilton

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.