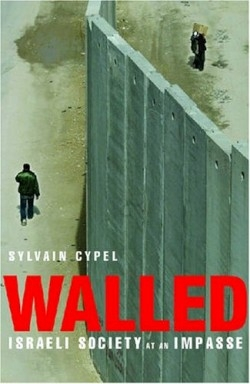

Walled

Israeli Society at an Impasse

In the summer of 2004, the International Court of Justice ruled that Israel’s security barrier violated humanitarian law. Three years later, the wall measures 252 miles and is growing. Supporters point to the fact that suicide bombings have nearly halted since the beginning of the wall’s construction; while opponents cite the land confiscated and homes razed in its wake as proof of its inherent injustice. For Sylvain Cypel, the wall is much more than a physical barrier. It is a tangible manifestation of the mental walls that Israelis and Palestinians have built over the past sixty years.

With the passion of an investigative journalist and the patience of a historian, Cypel describes how a culture of denial has strangled both societies. He focuses on Israel’s failures in particular, addressing pivotal events such as the war of 1948, the Six-Day War, and the failed peace talks of Oslo and Camp David. In each case, the author analyzes the key players involved and explains why their own mental blocks have sabotaged the peace process. Cypel’s position is that Israel has whitewashed its account of these events, thereby damaging its international credibility, hardening its citizens and masking the real issues at stake.

Currently a senior editor for Le Monde in Paris, Cypel dedicates twelve chapters of his analysis to Israel and two to the Palestinians, while two concluding chapters discuss both. As a Jew and former resident of Israel for twelve years, the author claims a more intimate understanding of the society. He holds degrees in international relations, sociology and contemporary history and is the former editor-in-chief of Courrier International.

Over the past twenty years, many scholars have challenged Israel’s official claims about the Palestinian occupation. Cypel’s work is unique because he extends the debate beyond governmental failures to broader sociological phenomena. The author contends that the symptoms of occupation have brutalized an entire generation in Israel. He points to the censorship of Israeli textbooks, religious ultra-nationalism and rising rates of crime and spousal abuse as proof that this legacy of domination is slowly unraveling the culture from within. In one of his most powerful chapters, Cypel underlines the Shoah (Holocaust) as a defining historical moment for the nation and explores how the collective memory of this event continues to impact Israel’s self-awareness.

International opponents often compare Israel to the Third Reich, a practice that Cypel calls “not just an absurdity” but a “perversion.” At the same time, he argues that the state of Israel has appropriated the memory of the Shoah as its exclusive moral domain, attacking outside analysis and refusing to recognize how its lessons might shed light on the injustice of the occupation. “As for the extermination of the Jews of Europe,” Cypel writes, “it is no longer a specific human and historical tragedy but an immaterial armor, without tangible representation, of permanent victimhood.”

Cypel’s discussion of Palestinian society is brief, but absorbing nevertheless. He cites rampant anti-Semitism, paralyzed leadership, suicidal terrorism and a lack of realistic self-analysis as factors that have all hampered the fight against occupation. Still, Cypel tries to show that Israel has done everything in its power to ensure that chaos and corruption reign in Palestine. According to the author, hardline tactics such as the targeting of Palestinian pacifists and the routine closings of schools have made daily life in the territories unbearable and advanced the appeal of extremism.

Cypel’s attack of Israel is often scathing, and there are moments when the book suffers from his harsh tone. The author sometimes fails to distinguish between the Israeli government and the Israeli people and oversimplifies the roots of the policies and attitudes he criticizes. Concerning Israeli discrimination against Arabs he writes, “This body of attitudes basically revolves around the imperative need to dominate the other, owing to the fear aroused by the thought of what would happen if this domination were to end.” Such vague points may confuse readers. Instead of exploring how forces such as psychological trauma might have shaped individual racism or how the desire to preserve a Jewish state leads to flawed democracy, Cypel only condemns the end result.

Originally published in French, Walled was awarded the twenty-third Francisco Cerecedo Journalism Prize for its Spanish translation. The accolade is no surprise. Cypel is a gifted writer, and his book is recommended for anyone with a background and interest in this timely topic. However, if the author hopes to effect real change in Israel, a more even approach might have been warranted. One fears that while Cypel’s passionate arguments are riveting, they may only incite more anger among Israel’s doubters and urge its supporters to build their mental walls stronger and higher.

Reviewed by

Aimee Sabo

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.