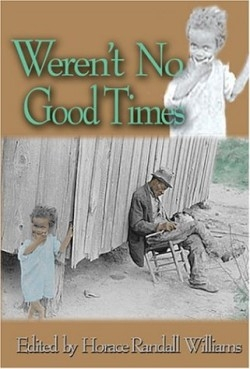

Weren't No Good Times Personal Accounts of Slavery in America

Authentic voices of slavery are audible in this book: “After I was free I didn’t had no marster to ’pend on and I was hongry a heap of times. I belong to the ‘federate nation an always will belong to yall, but I recon it’s jes as well we is free cause I don’t believe the white folks now days would make good marsters.” Many of the stories in this volume echo these words, from former slave John Smith of Alabama. Slavery was more secure than freedom, and masters were generally reliable—even those who could only be relied on to be cruel.

The editor, who founded Southern Poverty Law Center’s Klanwatch Project and directed it for many years, chose these narratives from more than two thousand archived during the 1930s by the Federal Writers’ Project. His goal was to counter Alabama’s tradition of filtering the history of slavery through myths of happy slaves and kind masters. Some slaves were owned by traders and treated like livestock. Others recall working during all daylight hours virtually every day of the year.

Many anecdotes do acknowledge kind treatment: masters send for white doctors when slaves become ill, or permit slaves to attend church. Yet they also make clear the value of emancipation. Cheney Cross remembers being reclaimed by her parents: “I never will forget ridin’ behin’ my daddy on that mule in the night. Us left in such a hurry I didn’ get none of my clothes hardly, and I ain’t seed my mistress from that day to today.” Similarly, Stepney Underwood received special treatment because his owners “useta think I was funny as a little monkey.”

The first narrative in the collection is by Nicey Pugh, who was still a child when the war ended, and it raises many of the contradictions experienced by slave children who were favored by their masters. Pugh recalls witnessing the brutal execution of a black man: “I knew it was a blessin’ to him to die.” However, she hastens to editorialize lest her white interviewers get the wrong impression: “Yassuh, white folks … [y]ou ain’t never walked acrost a frosty field in the early mornin’, and gone to the Big House to build a fire for your mistress, and when she wakes up slow to have her say to you, ‘Well, how’s my little nigger today?’”

For a century and a half, these stories and the truths they disclose have been hidden from view. They are far too important to stay neglected and ignored. Williams has resurrected the last generation of America’s slaves and allowed them to speak in their own voices.

Reviewed by

Elizabeth Breau

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.