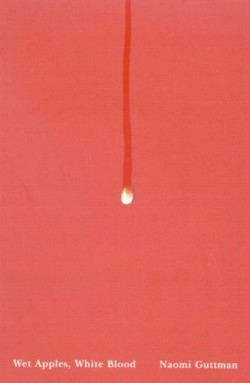

Wet Apples, White Blood

Throughout Naomi Guttman’s latest collection, Wet Apples, White Blood, the poet demonstrates an enthusiasm for history and motherhood. From the Virgin Mary to Medea, Guttman examines the full spectrum of mothers; with herself somewhere in that gray area between saint and murderer. Although these poems pay their respects to a variety of historical figures (fictional and otherwise), it is the mother whose wisdom is paramount:

Because the child knows in its soft bones

the details of his mother’s day

a pregnant woman must avoid

funerals and mourning, ravaged bodies

persons crippled by disease and poverty.

Above all, it is the mother’s duty to protect her child. This unspoken commandment is most forcefully on display in Guttman’s sequence Galactopoiesis (a medical term for the continued secretion of milk, which translates “milk making” or, more interestingly, “milk poetry”). This cycle of nine poems recalls the history of a child’s illness and his mother’s simultaneous necessity and futility. In “Incident Room,” the nurse trying to insert an IV suggests the mother leave, maintaining, “He thinks you’re going to save him.” The mother replies, “I am. I will.”

Guttman tells the painful story of the infant’s illness deliberately, making her readers feel the mother’s obsession with his health so much that the appearance of another child—at home, turning toward the wall to sleep—is surprising. What is this healthy young girl’s role in the story? It is nearly impossible not to associate her with the earlier appearance of a son’s rival sister in the title sequence, “Wet Apples, White Blood.” In “On the Difference Between Boys and Girls,” Guttman exposes the bitter irony of a girl child being outranked by her brother who is breast-fed while she gets bottles and grows weak from them. It is a sly response to the poem’s title; yes, the baby girl may be getting the short end of the stick and all the gender-bias that goes with it, but the rest of Guttman’s collection suggests that women have an innate power in their ability to produce and provide nourishment. Only women have white blood.

Even though the second half of this collection’s title is explained as a neighbor’s phrase for breast milk, the affect of the wordplay is not lost. There is a strangeness here that results from the intentional misuse of single words. In the prelude poem “Prayer”: “Rest your ribs / into my hands” (rather than “on my hands”) followed by “Sing your sweetest throat” (rather than “sing your sweetest song”). In such moments, Guttman lays claim to the title of both poet and mother, and “milk poetry” makes more sense than ever. “For Rent” most obviously shows the poet’s ties to the tradition of her art. It is a glosa of Rainer Maria Rilke’s poem “Evening in the Park,” and Guttman uses her inspiration wisely, adding lines such as “The city breathes like one who’s eaten well” to complement the ones lifted from Rilke. But Guttman is far beyond name-dropping in proving her poetic seriousness; she skillfully employs form and rhyme, producing a ballad and a sonnet as well as a plethora of neatly rendered tercets.

In many ways, Wet Apples, White Blood is an appropriate follow-up to Guttman’s award-winning debut collection, Reasons for Winter. If Reasons for Winter circles around themes of intimacy (particularly from a female perspective), a collection circling around themes of motherhood is the natural result. Perhaps it is this very appropriateness that allows Guttman to avoid the falling-off that is all too common among poets’ second books. Or perhaps it is her patience, evident in the speaker’s attention to her ailing son, that saves her. The conflation of being a mother with being an artist is certainly present throughout this new collection. While the trope of poet as mother (or father) may not be new, Guttman’s subtlety makes the association seem genuine. In “Mrs. A’s Vegetable Stand,” Mrs. A offers:

white blood, which illustrates how we make

them ours, write them even after birth,

with fluid drawn from flowering

chest ducts, how we coat

soft sinews with muscle and fat.

It is only that little word “write” that recalls “galactopoiesis” means “milk poetry” as well as “milk making.” A poem belonging to that cycle, “Ward,” reveals why a woman who does not pray would open her collection of poems with a prayer: “Who knows but words / could heal?” Thus, through this hope of a mother, Guttman expresses the hope of all poets.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.