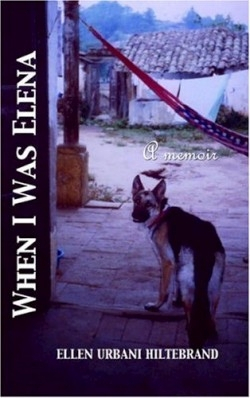

When I Was Elena

The author arrived in Guatemala in 1991 a fresh-faced twenty-two-year-old, straight from life as a southern belle at the University of Alabama. She left at the end of her two-year Peace Corps stay as Elena (so nicknamed by the Guatemalans she met), a woman forever changed.

In this book, labeled a memoir but transcending traditional genre, Hiltebrand tells the story of her Guatemalan years. As a memoir—fiction—guidebook hybrid, the novel contains chapters written from Hiltebrand’s perspective interspersed with fictional imaginings of first-person tales from seven women (six indigenous and one fellow volunteer) she meets in Latin America.

With the volatile political environment as a backdrop, Hiltebrand integrates herself into community life in the poor rural villages as closely as a white woman—a gringa to the natives—possibly can. Teaching in a school, she tries to make a difference, but learns the limits of her power to effect change, as when a young girl shows signs of physical and sexual abuse and Hiltebrand can do little to help. Struggling with the near-constant threat of sexual violence and envy of those around her (neighbors would regularly root through her personal belongings, taking whatever they fancied), Hiltebrand also experiences generosity in the face of overwhelming poverty, as when a woman kills her own chickens to feed Hiltebrand’s sick dog.

Hiltebrand’s lovely, inventive prose makes even something as simple as the arrival of evening feel charged: “Darkness hugged tight to the ground and night loomed hot and dry.” No less thrilling than Hiltebrand’s discovery of the physical terrain of Guatemala and its people is her discovery of the terrain of herself. She writes of her motivation: “I came to Guatemala to find me—all the vast possibilities of me,” and her self-exploration is fascinating. She is unflinchingly tough on herself—skewering her own preconceived notions of Guatemala—thereby balancing out the portions of the book where she treads a mite too close to being self-congratulatory.

Seventy volunteers reported for Peace Corps duty alongside Hiltebrand, yet by the end, fewer than twenty remained. Volunteers were raped, robbed, and murdered; some simply gave up and went home. Ellen Hiltebrand survived and documented that journey. It is somewhat troubling that she puts words in the mouths of the indigenous women; one imagines that her evocative writing would have resulted in a strong story solely from her perspective. But Hiltebrand deserves praise for telling both her own story and that of those who, because of the collective din of poverty, war, and misogyny, would otherwise never have been heard.

Reviewed by

Iris Blasi

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.