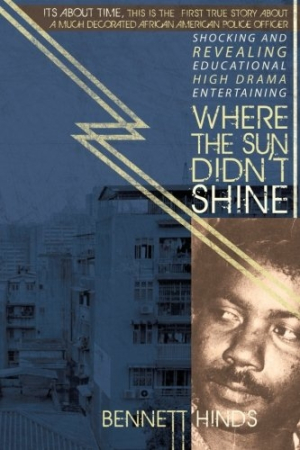

Where the Sun Didn't Shine

“We are here because the Puerto Rican and black community asked for us. Well, they got what they asked for. We will make ourselves known loud and clear to the pushers. God help them, the PEP Squad has arrived.” Created in the late 1960s, the Preventive Enforcement Patrol, a handpicked group of twenty of New York City’s minority cops, patrolled the most dangerous streets at the most dangerous times to seek out and bust some of Harlem’s most dangerous criminals—in the name of racial harmony and good community relations. Unfortunately, as author and former cop Bennett (Benji) Hinds records, the helpers became the targets. Hinds was a member of PEP. He walked the walk, and now he is talking the talk.

The NYPD launched PEP in response to mounting pressure from minority residents to eliminate the insidious drug cartels operating with impunity in Harlem. Hinds, a relatively new policeman known for occasionally bucking authority, believed in the ideals behind PEP. A Trinidadian who grew up in Brooklyn, himself a mugging victim, he wanted to make the city safe. In gritty gun fights and backroom deals, PEP brought down a major drug lord and a corrupt black politician. The success came at a cost: Hinds’s best friend had his brains blown out, two other PEP members were also killed, and one was injured for life.

PEP operatives were never officially recognized for performing the same daring exploits that many white officers were routinely awarded for. Instead, Hinds and his black and Hispanic fellow crime fighters were “rewarded” with attacks by intractably racist white police who wanted PEP to fail. “Friendly fire” was the reason often given when a cop of color went down. On one occasion, Hinds was lured into a nearly fatal shootout after a white cop handed him a radio with defunct batteries. At times, white police ignored PEP calls for backup. Eventually, these attempts to undermine and even destroy PEP and its members from within became too obvious to be ignored. But there was no sympathetic ear among the higher-ups. Hinds and his fellow PEP comrades were promised promotions that never came.

Where the Sun Didn’t Shine is highly readable though not unflawed. There is mention of Hinds meeting with someone “who was going to help write his book,” but no ghost is credited. A few annoying verb tense disagreements are also apparent, as in, “Travis body is chalked, and then he was slid into a heavy plastic body bag.”

In general, though, this true-crime tell-all is hammered out in short, action-packed chapters that are filled with the sounds of gritty police talk, harsh street slang, sirens, and gunfire. From page one the reader is immersed in the story of an idealistic young policeman enraged and frustrated from harrowing showdowns with the bad guys, and stealthy attacks by the so-called good ones. The chaos and violence of the street is contrasted with Hinds’s personal life as his attempts to maintain a calm, fulfilling romantic relationship slowly deteriorate because of the mind-numbing stress. By the end of the book, readers know Benji Hinds very well.

Hinds avers that corroboration of his story can be found in NYPD operational files. The author’s moral kinship with NYPD’s legendary undercover cop Serpico is highlighted in a (possibly imaginary) conversation between the two men. That is certainly a connection that Hinds would like to establish. A fast-paced and still topical memoir about hidden racism, Where the Sun Didn’t Shine would make dramatic cinema.

Reviewed by

Barbara Bamberger Scott

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.