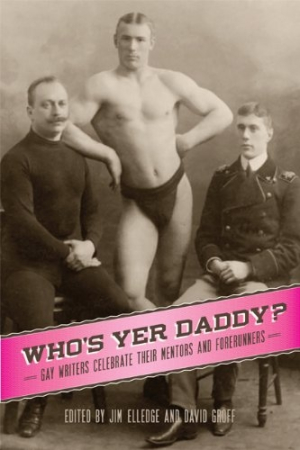

Who's Yer Daddy?

Gay Writers Celebrate Their Mentors and Forerunners

“Influences are of course not simply a list of books read, but, as the word suggests a flowing into. It might be a rambling, a series of confluences.” In his contribution to this anthology, Greg Hewett further suggests that if the evolution of any writer includes significant interactions with specific texts, those experiences are all the more meaningful for young men struggling to understand their sexuality and its place in their writing. Hewett recounts being too embarrassed to check out Jonathan to Gide: The Homosexual in History, released in 1964, from his public library; instead, he has lived for years with the guilt of stealing the “731-page tome” by shoving it “in the waistband of my carpenter jeans.”

Frank O’Hara is the “daddy” mentioned most frequently, but the lists of muses provided by the thirty-eight contributors are long and inclusive, not all gay, and not all male. It seems that a “daddy” can be anyone, and “queering” the meaning of a word is certainly well within LGBT tradition, especially when the reader is a gay high school or college student desperate for any glimpse of himself and others like him on the page. W. H. Auden, Jean Genet, Walt Whitman, Paul Monette, Tim Dlugos, Allen Ginsberg, Herman Melville, James Baldwin, Gertrude Stein, Audre Lorde, Joy Williams, Sylvia Plath, and others too numerous to be named here have all served as “daddies” for emergent gay writers, providing hope that there is a community to which they can belong as well as important insights about how to wield their pens effectively, provocatively, and honestly.

But more than the famous are honored here: English teachers and other mentors are also memorialized. Ms. Oliver gave Charles Jensen “exactly the degree of criticism I could handle at that point,” and Ellery Washington grieves the sudden death of Ms. Briscoe, who introduced him to Melville and laughed when he finally came out, asking, “So when did you figure it out?”

The multilayered literary history encompassed in these pages will also resonate with readers who are not necessarily gay men but possibly straight, lesbian, bi-, trans-, or non-conformists, because their influences comprise a constant flow of ideas, identities, and affirmation. Even if a given reader has not been “bombasted by Whitman,” or mourned the loss of a lover to AIDS, he or she may recall similar connections to the works of other writers, encountered alone or in class at crucial moments. As these writers pay homage to their “daddies,” readers will revel in their sheer love of letters and the centrality of the written word to constructing meaning and identity for all of us.

Reviewed by

Elizabeth Breau

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.