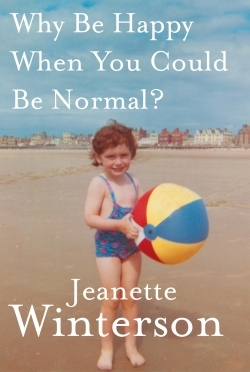

Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?

Readers familiar with Jeanette Winterson’s semi-autobiographical first novel, Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, know a scumbled version of her history: Adopted by a religious fanatic and her passive husband, forbidden to read much beyond the Bible, thrown out of the house at

sixteen when her lesbianism was discovered,

and ultimately redeemed by the written word. Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?

is told firsthand with no fantastical diversions

or adornments. It’s often bleak, but also very funny and as beautifully crafted as any of Winterson’s fiction.

The difficulties of her home life included physical abuse and being locked out of the house or in a coal scuttle overnight, but Winterson describes the core conflict with her adoptive mother as “the battle between happiness and unhappiness.” Despite the dual grinds of poverty and cruelty, Winterson describes herself as staunchly in love with life and seems set out to prove it, walking in the woods all day with no more than a jam sandwich and milk for fuel, or making up stories to pass the time in the freezing “coal hole.” The book’s title seems as if it could be allowing for a kind of mixed happiness that takes these divergent extremes into account; in truth, it’s the last thing Winterson’s mother said to her as she kicked her out of the house, after an exorcism failed to cure her homosexuality. In Mrs. Winterson’s world, happiness and normalcy were as far apart as Earth and the moon.

On her own at sixteen, Winterson managed to finish school while living in a car, then make her way to Oxford and literary success by the time she was in her mid-twenties. These victories didn’t put the past to rest, or even salve its wounds. After a difficult breakup she “began to go mad,” suffering a debilitating mental illness and suicide attempt before beginning a search for her biological mother. Her mission is successful but leads to more questions than it answers. The book’s last line could be true of any human—“I have no idea what happens next”—but it seems a uniquely Wintersonian choice for both its honesty and willingness to accept ambiguity as a fact of life.

Reviewed by

Heather Seggel

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.