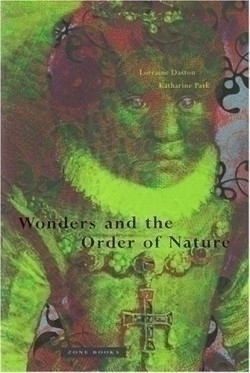

Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150-1750

Until the rise of modern science, “wonders” played powerfully on the public mind. They included marvels, miracles, monstrous births, mariners’ tall tales, explorers’ fantastic reports, comets and every sort of portent, prodigy and aberration of nature—to say nothing of basilisks, bezoars, manticores, luminescent Bolonian stone, spontaneously generated gold teeth, Mexican foot jugglers, scrotum stones and camels that obdurately refused incestuous unions.

In this fascinating book, Lorraine Daston and Katharine Park take the reader on a skillfully navigated voyage through the changing responses in the European mind to all that was mysterious, miraculous and inexplicable. The credulous acceptance of medieval folk gave way to a cooler curiosity and finally, in the Enlightenment, to critical analysis and rejection of the strange. Against an unfailingly colorful backdrop of cited wonders, the authors record the changing realities and phenomena that made up wonders, the differing sensibilities that shaped society’s response, and the response itself as a molding force in life and politics. Though the cast is immense (Aristotle to Newton, St. Augustine to Hobbes) and the canvas huge, the thread of argument remains clear and strong. With enduring curiosity, man fixed upon wonders, sought to understand and categorize them, and finally dismissed them.

Monastic chroniclers and encyclopedists eagerly seized upon the reports of domestic and foreign travelers for new wonders—dog-headed men, cannibals, wonder-working springs among them. Distance diminished doubt: Who questioned tales of the Tartars? Who trod in Mandeville’s footsteps to deny his many marvels?

In a strikingly modern way, wonder soon became commoditized: Princes wanted the nautilus shell, the griffin’s claw, the unicorn’s horn, the healing gemstone and other wonders to reflect their power and prestige and to dazzle any incoming embassy. Prelates wanted these and similar items to enrich their churches and accommodate or decorate the relics of saints, thereby impressing the faithful. Aggressive collecting, trading, and ranking wonders by rarity entered the business.

Wonders gave rise to thwarted curiosity, particularly when they were aberrations of God’s finest creation—man and animals. Though Aristotle had dignified curiosity as the moving force of enquiry into phenomena and ideas, Catholic theologians of the 13th to 14th centuries generally did not look kindly upon any questioning of God’s more mysterious acts. The authors trace how philosophers and natural scientists increasingly shied away from questioning what lay outside or beyond normality, a trend not fully reversed until the burgeoning of empirical enquiry in the 1360s and thereafter. By then a more practical focus was appearing, even in Italy—a concern for the observable effects of spring waters, minerals and medications dear to the population.

Marco Polo’s manuscript on his travels in the Orient and Christopher Columbus’ reports from the New World in turn proved to be useful catalysts to the broadening wonder industry, giving rise to new speculations about the natural phenomena of the Old World. Natural history, phenomena and wonders occupied the Italian academies, while the far-ranging writings and analyses of physicians, scientists and inventors and their correspondents provided challenging insights into topics new and old.

Aggressive collecting took on a new life in the 16th and 17th centuries. Wonders, as such, experienced a late flowering with the rise of wunderkammern (essentially domestic mini-museums) as a must-have for any self-respecting monarch.

A pre-Enlightenment rationality entered the picture when Bacon and Leibniz argued that wonders and curiosity about them are fine for ordinary folk, but were not the real business of science. Thomas Hobbes’ classifying mind and René Descartes further promoted rational enquiry. Later, the foundation of the English Royal Society and the French Académie Royale des Sciences—with their networks of correspondents and investigators and their increasingly scientific agendas—demanded concrete data, reliable witnesses and rigorous analyses to accompany reports of wonders. Within a century, wonders became the stock in trade of the Aladdin’s cave of the past.

In Wonders, Daston and Park have produced a scintillating scholarly work of very broad appeal. While some of the philosophical and structural under-pinnings may tax lay readers (such as this reviewer), the authors point to avenue after avenue of stimulating exploration. Last but not least in an age of cheap production, Wonders is an exceptionally handsome book in size, design, layout and typography, brilliantly illustrated. Zone Books deserve congratulations, and Bruce Mau Design Inc. should surely win the cover-of-the-year award for the evocative, haunting book jacket.

Reviewed by

Peter Skinner

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.