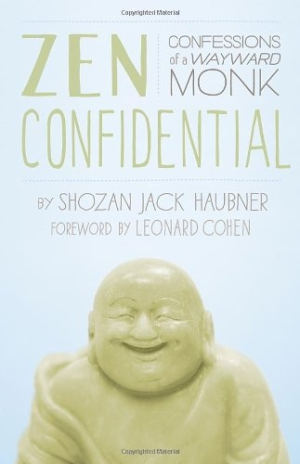

Zen Confidential

Confessions of a Wayward Monk

Memoir of Zen Buddhist debunks myth of the monk as a person who has sacrificed a “juicy” life, with dark humor and an exploration of anger and deviance.

This slender collection of essays is a showcase for Haubner’s abilities as a storyteller, if not a memoirist. The dozen or so pieces range in quality from admirably candid to downright disturbing. Zen Confidential is out to debunk “the popular stereotype of the monk as someone who undergoes a spiritual lobotomy” and finds contentment at the expense of an interesting and “juicy” life.

Haubner’s route to Buddhism demonstrates the validity of that idea. Raised in a conservative Catholic family, he moved from the Midwest to LA, trying his hand as a screenwriter and stand-up comic before stumbling upon the path that led to a Zen monastery in California, where he now lives. The colorful detours he takes on this path compose most of his narrative. He works the margins of American society, depicting the disillusioned and addled, the deviant and devout, bringing his own earthy, irreverent humor to the mix. He has a flair for description, such as the girlfriend with the blowtorch eyes and the gay monk on meth who is his beloved mentor.

As Haubner says, “A lot of pissed-off people wind up at our monastery.” His own seeds of violence were planted by a father who made and sold gun barrels, enmeshing his family in a subculture of John Birchers, urban warfare survivalists, and the religious right. In the most engaging essay, “A Zen Zealot Comes Home,” which appeared first in Sun magazine, the pain of estrangement hits him hard, though he discusses it with blithely offhand humor: “Every year I prove right that old Zen adage: Think you’re getting closer to enlightenment? Try spending a week with your parents.” By the end, he realizes that Zen practice, like life itself, is not about floating above your problems, but passing through them.

Winner of a 2012 Pushcart Prize, Haubner calls himself “a loner who hates to be lonely.” Like many who gravitate to Zen Buddhism, he has an admitted antisocial streak but is willing to look unflinchingly at who he has been before he can embrace or face who he is at present. In the vein of Rousseau’s autobiographical confessions, he shows what happens “when a group of people with anger issues decide to engage in a practice that deprives them of sleep, comfort, personal space, protein, Internet access, and even their hair.”

There is an irony to all that long training in the art of self-forgetfulness having led to this public airing of his “adventures in self abuse.” But perhaps, like in Japanese archery, the target is not necessarily the thing that is being shot at—it is a contest of the person with himself.

Reviewed by

Trina Carter

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.